Before we get into the how of assessing key competencies for sustainability, let’s first look at the why (other than that is part of what we get paid to do, and that students need to somehow get certified for courses we teach in order to complete their studies). Assessment always also serves a double purpose with regard to improving both learning and teaching: It gives students an idea of how they are doing in relation to teacher expectations, and it gives the teacher feedback on how well their teaching is working.

Of course, these last two points are really difficult in practice. Is what we measure really aligned with what we are hoping students will have learned? And can we even measure what we have hoped they have learned? If we think about Teaching for Sustainability as mainly teaching key competencies, i.e. embedded performances or internal cognitive processes, rather than disciplinary content (often factual), we face a task that is both exciting and challenging. How are we going to teach and assess competencies like whether someone can think in systems or envision different futures in ways that actually capture that competence fully? I don’t have all the answers, but here are some thoughts.

First, let us start backwards and “constructively align” our instruction by thinking about the Intended Learning Outcomes, how we would know if students meet them (i.e. the assessment), and then lastly how we might actually go about organising teaching and learning so students have the chance to show us in the assessment that they have met the learning outcomes (i.e. the learning activities).

Intended Learning Outcomes: Key Competencies for Sustainability

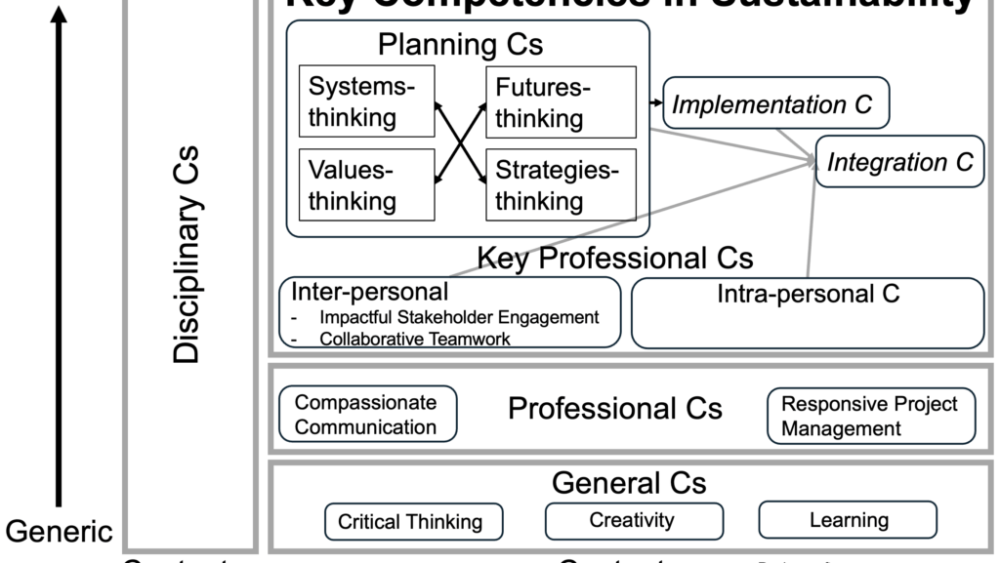

Let’s say our learning outcomes are key competencies for sustainability. There are several frameworks in the literature that have converged so much over time that it does not really make a difference which one we pick, so let us just go for the one by Redman & Wiek (2021).

One thing is always important to mention about this framework: Areas in the figure are obviously neither proportional to importance of competencies, nor the time that should be spent on each!

With that out of the way, the framework in a nutshell: Students always learn a lot of disciplinary competencies that range from fairly generic to highly specialised. But they also need content-independent general and professional competencies, like for example critical thinking (an all-time favourite!) or good communication skills. They also need to develop and practice inter-personal and intra-personal competencies, and that is where we come into the realm of key competencies for sustainability: Together with planning competencies and implementation competencies, they can become integrated competencies. The key here is that while competencies can be practised each on their own to some extent, they need to also be practised together. Btw, note how all these competencies seem to make a lot of sense to master to be prepared for what the future might bring, regardless of whether we want to tackle sustainability challenges (There is an almost complete overlap with the requirements of the 1993 law that sets the requirements for a Swedish Master of Science in Engineering!). So it’s basically the common-sense understanding of preparedness for the future put into a framework that shows how the competences build on and relate to each other and to disciplinary content.

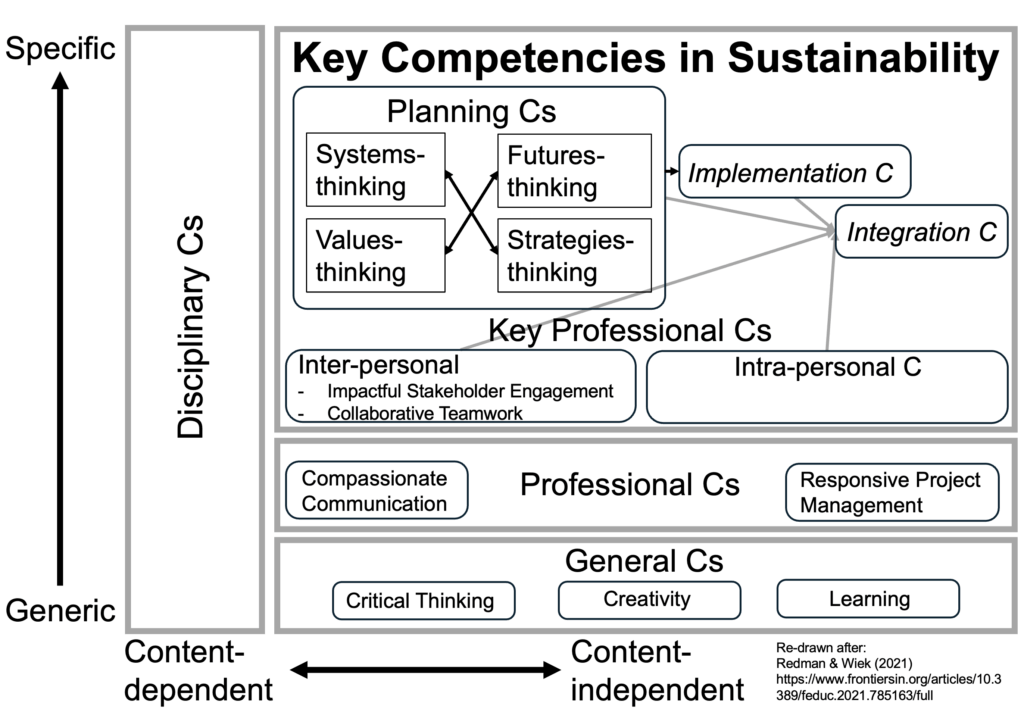

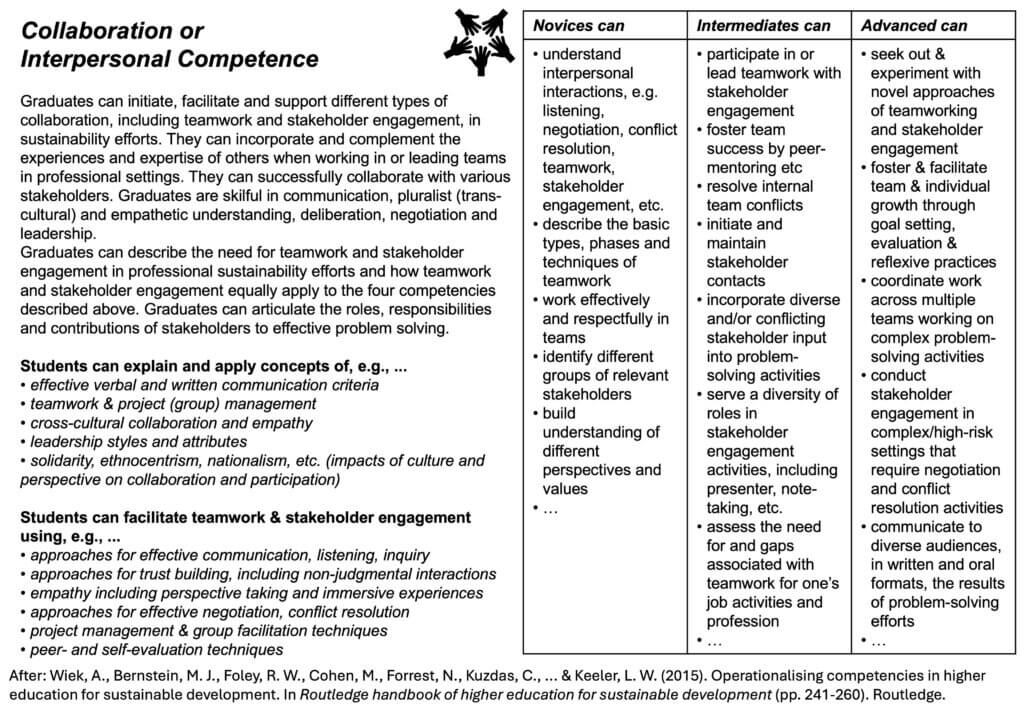

But what do those competencies entail in detail? Some of them were operationalised for higher education in Wiek et al. (2015), which is very helpful (and also a little scary because there is so much that we should be able to do!) Below, I am sharing one slide on collaboration (or interpersonal competence) because it feels like the one competence that we might be most familiar with, both when it comes to our own skills and teaching it. I share similar slides for the other competencies here.

In the levels of “novices”, “intermediates” and “advanced learners can …” is some kind of progression indicated, maybe with novice being incoming students and advanced what students will have mastered over the 5 years of a program. And of course we can also consider whether all these competencies need to be mastered by everybody, or whether we should rather count on working in teams with distributed expertise, as Wiek et al. (2011) suggest (and to be fair, the article is specifically about sustainability programs). In any case, the Wiek et al. (2015) article provides a very detailed account of how each of the key competencies can be operationalised, and that is a great start that then every teacher, every program needs to adapt to their own context to formulate their Intended Learning Outcomes on module, course, program level. But keep in mind that practising elements in isolation is not enough, they need to also be practised in an integrated way. So there needs to be some progression over time.

Now, let’s assume we have formulated the Intended Learning Outcomes. How would we be able to know if students every achieve them?

Assessment Tools

This is actually a really difficult question. Redman et al. (2021) gives an overview over common assessment tools, which I summarise in the slide below. But note that this is study about what is most common, and then discussing pros and cons, it is not a necessarily a list of what is most desirable!

So far, so good! But now we need to combine the assessment tool with some form of assessment criteria. I recently wrote a longer blog post on the topic where I show different rubrics from the literature (and I found it really interesting, so you might want to check it out), but what I think is most important to consider is what indicators can we observe that someone has learnt “enough”, and how we set the relative importance of showing one indicator vs not showing another one.

One distinction that I find helpful when thinking about this is whether we want to measure or judge a student performance (you might want to read Hagen & Butler (1996) on this). In a measurement mindset, we assume that we can actually find objective measures of performance, whereas in a judging model we rely on holistic assessment by experts. But to ensure fairness, even those experts need to communicate about their criteria and indicators, and make sure they are more or less on the same page. So developing a rubric might still a good idea (and this might of course include negotiation with students both to give them ownership and to ensure that they know what is expected of them).

I am not sure if I want to open this can of worms here and now, but the thought of student ownership of assessment leads me to a thing called “sustainable assessment“. In a nutshell, it means an assessment that is useful to learning beyond the frame of the course it is related to, not just in terms of retaining the learnt information and skills for longer, but to support future learning. Of the assessment tools in the figure above, “reflective writing” might be the most obvious candidate for sustainable assessment, because it includes learning to identify where someone is at, where they want to get to (whether that is to reach our Intended Learning Outcomes or maybe explicitly and purposefully something else), some thoughts about how to get there, and thoughts looking back evaluating how things went, and then using this to plan future steps. The skills learnt in that process can obviously be useful beyond just the one course where reflective writing is used as assessment tool.

And of course, a summative assessment situation should never be the first time that students are faced with a specific type of task, so the assessment should be tied in, and practised with, the learning activities.

Learning Activities

This is probably where the overwhelming majority of literature has their focus, but usually without explicitly connecting them to either ILOs or assessment.

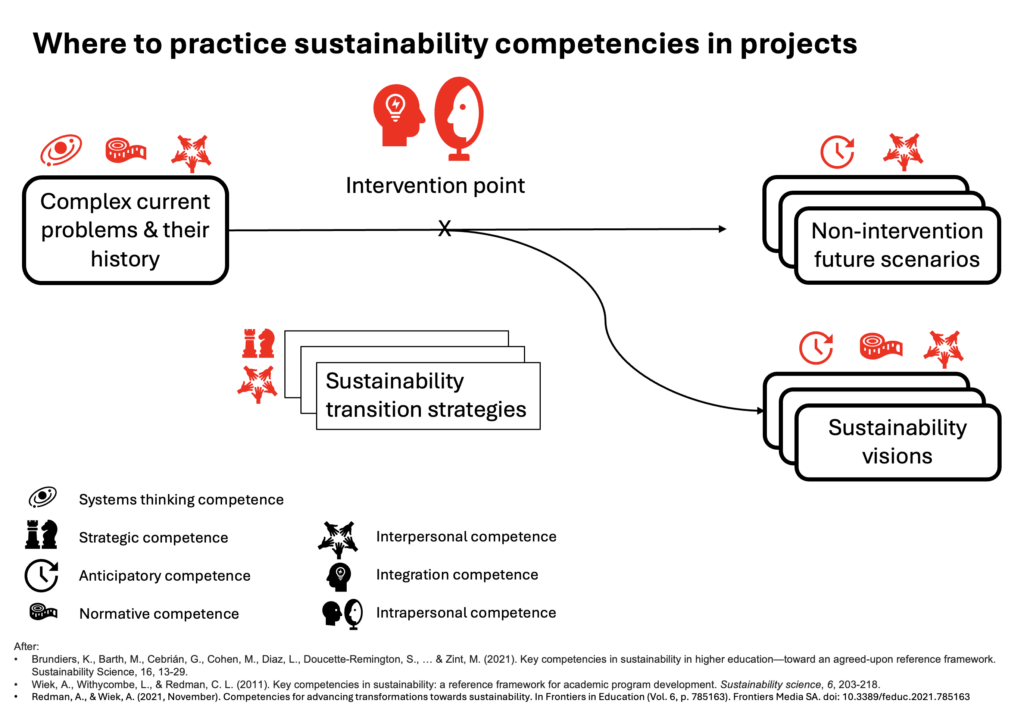

I like to use the figure below, which I re-imagined after Brundiers et al. (2021) (now that I know I didn’t invent it myself…), to show where, in a typical project, each sustainability competency can be practised, and how some of them necessarily have to go together.

For example, to understand a complex, current problem and how it came to be, we do need systems thinking, but we also need interpersonal competence to be able to talk to, and empathise with, people who maybe were part of creating the problem (or just people on our team who also want to understand the problem!), and normative competence so we understand what values led to the status quo. Similarly, to envision both intervention and non-intervention futures, we need to have anticipatory competences. Developing strategies requires obviously some strategic competence, and at all stages we need to be able to understand and work with other people, and also ourselves. And this is obviously the most simplified way of talking about those competencies, I would like to remind you of their operationalisations I mentioned above…

And in the end, in most learning activities, we go from some input through some process to some output. And in those steps, we can always practice all those competencies if we open up for it, for example by including opportunities to communicate with peers or people that we might not typically communicate with, or to relate things to our own values or understanding of the world. However, some pedagogical approaches are more likely to be connected with learning of sustainability competencies than others (see Lozano & Barreiro-Gen, 2022, or my summary). For example working with case studies means that we can simultaneously get insights into specific cases (ha!) from industry or anywhere else and practice disciplinary skills and acquire disciplinary knowledge as well as sustainability competencies, whereas “just” calculating a solution might practice relevant disciplinary skills, but is a missed opportunity in terms of practising sustainability competencies.

A suggested approach

Steven Curtis shared his suggested general approach to assessment in the ISCC course:

- Identify relevant competence(s) clearly expressed in ILOs

- Select assessment methods that align with chosen competence

- Ground assessment tasks in real-world contexts

- Create rubrics with transparent criteria for each competency level (e.g. novice, intermediate, advanced)

- Include opportunities for reflection and peer feedback

- Collect and analyse student performance to refine and improve teaching

- Use iterative assessments to support ongoing competency development

With this — good luck, and please don’t hesitate to be in touch if you have questions or comments, or just want to discuss!

Brundiers, K., Barth, M., Cebrián, G., Cohen, M., Diaz, L., Doucette-Remington, S., … & Zint, M. (2021). Key competencies in sustainability in higher education—toward an agreed-upon reference framework. Sustainability Science, 16, 13-29.

Lozano, R., & Barreiro-Gen, M. (2022). Connections between sustainable development competences and pedagogical approaches. In Competences in Education for Sustainable Development: Critical Perspectives (pp. 139-144). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Redman, A., & Wiek, A. (2021, November). Competencies for advancing transformations towards sustainability. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 6, p. 785163). Frontiers Media SA. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.785163

Redman, A., Wiek, A., & Barth, M. (2021). Current practice of assessing students’ sustainability competencies – a review of tools. Sustainability Science, vol. 16, pp. 117-135.

Wiek, A., Withycombe, L., & Redman, C. L. (2011). Key competencies in sustainability: a reference framework for academic program development. Sustainability science, 6, 203-218.

Wiek, A., Bernstein, M. J., Foley, R. W., Cohen, M., Forrest, N., Kuzdas, C., … & Keeler, L. W. (2015). Operationalising competencies in higher education for sustainable development. In Routledge handbook of higher education for sustainable development (pp. 241-260). Routledge.