What clash? Carbon emissions must not exceed 2 tons carbon per capita by 2030 to stay within 1.5 degrees of warming, which is at odds with study abroad. One transatlantic flight emits about 1.6 tons of carbon. Yikes. Therefore, climate-focused study abroad relying on high-emitting travel poses a dilemma between study abroad and emission reductions. I investigated this dilemma as part of my MSc thesis for LUMES (Lund’s International Master’s Programme in Environmental Studies and Sustainability Science) looking at 156 climate-focused study abroad syllabi, surveying international climate educators, and interviewing affiliates of the Climate Action Network for International Educators. I considered whether studying climate change abroad is compatible with sustainability transformations for low carbon futures. The proceeding blog post is a summary of the study as it pertains to education for emission reductions.

Personal Clash

Originally from New York, I am an international educator—teaching International Baccalaureate students Environmental Systems and Societies, a course which prepares students with a “perspective of the interrelationships between environmental systems and societies,” and enables students “to adopt an informed personal response to the wide range of pressing environmental issues that they will inevitably come to face.” Further, I am also a graduate of the international Sustainability Science program LUMES. On the one hand, studying abroad is praised for equipping students with global perspectives, global citizenship, and intercultural exchange opportunities…on the other hand, it comes at a high carbon cost. The carbon cost of student mobility at large is up to 14 megatons of carbon/year. That’s equivalent to the emissions of entire countries like Jamaica! I am professionally and personally deeply embedded in the paradox of climate-focused international education which inspired my curiosity for this master’s thesis.

Education for Transformation

Education can be a key enabler of systematic behavioral change through knowledge dissemination, innovation, and social justice (Frick et al., 2021; Hale, 2019; Hindley, 2022). The institution of higher education plays an important role in promoting societal transformation by equipping the next generation of leaders and citizens for climate action (Leichenko & O’Brien, 2019; Leichenko & O’Brien, 2020; Shields, 2019; Stephens et al., 2018). However, educational research suggests climate change education falls short of teaching high-impact climate actions such as flying less to reduce personal carbon emissions (Kranz et al., 2022; R. Leichenko et al., 2022). The dilemma between study abroad programs and climate change has been studied in recent years (Campbell et al., 2022.; Feldbacher et al., 2023; Shields, 2019; Zhang & Gibson, 2021). However, less is understood about the potential of climate-focused study abroad for equipping students with the knowledge and skills for reducing carbon emissions.

Facts, Feelings, and Action for System Change

Climate scientists and educators alike advocate for the alignment of facts, feelings, and actions for effective learning and transformative change (Islam et al., 2022; Landon et al., 2019; Leichenko & O’Brien, 2019; Nicholas 2021; Tan et al., 2021). Research shows that further knowledge about climate change does not necessarily mean people act in alignment with the climate (Knutti, 2019; Leichenko & O’Brien, 2019; Wolrath Söderberg & Wormbs, 2022). To overcome this, environmental behavioral research shows that overcoming barriers of inaction requires integrating facts and feelings for climate action (Fraude et al., 2021; Woiwode et al., 2021; Wolrath Söderberg & Wormbs 2019). Thus, tapping into feelings and personal beliefs is essential for understanding individual and collective agency for sustainability transformations (Leichenko & O’Brien, 2019).

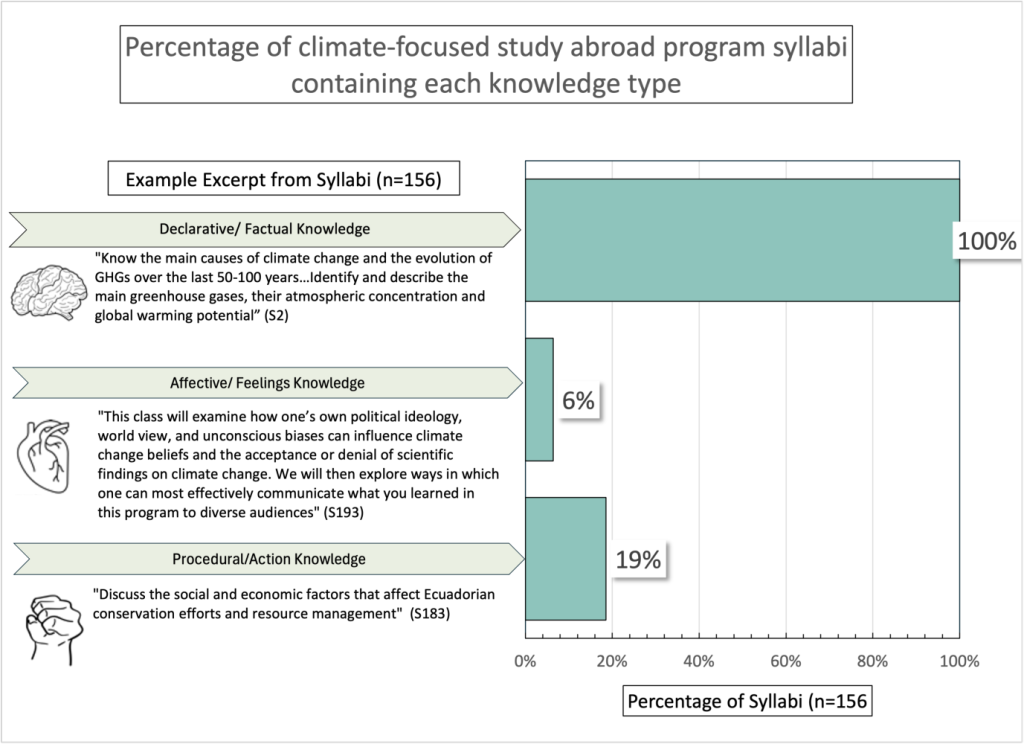

Knowledge and Skills in Climate Education

While education is key for transformation, we inadequately teach students the knowledge and skills for low-carbon futures. Study abroad courses related to climate change include themes of collaboration & communication, cross-cultural/global perspective, interdisciplinarity, place-based learning, risk assessment and management, solution-oriented learning, and systems thinking which mirrors the language of sustainability science but neglects concrete climate-action knowledge. Study abroad courses related to climate change teach factual knowledge e.g. “fossil fuels contribute to climate change”. Very few courses talk about feelings or approaches to climate action (e.g. eating a plant-based diet, flying less).

| Knowledge & Skills | Inductively defined within the coded knowledge types and pedagogical approaches | Example Excerpt in Syllabus | Syllabus reference | |

| 1 | collaboration & communication | mention of collab* or communica* | “Integrates the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes to learn interpersonal communication techniques.” | S13 |

| 2 | cross-cultural and/or global perspective | Including internationally minded, multicultural, global understanding, exchanging information from different cultures, cross cultural | “Understand international environmental politics at local, regional and global scales.” | S60 |

| 3 | interdisciplinarity | integration of multiple disciplines either content or methodological approaches | “Ability to encourage the knowledge of ecology with the integration of other social and biological sciences” | S17 |

| 4 | place-based learning | learning topics related to the location of study and in the place of study | “By undertaking field trips to various conservation project sites, students gain first-hand information about different conservation challenges and approaches from diverse stakeholders such as decision-makers” | S162 |

| 5 | risk assessment & management | assessing risks/management of climate impacts (e.g. extreme weather events, sea level rise, food) | “and the role of risk assessments in risk-reduction strategies.” | S193 |

| 6 | solution-oriented learning | mention of solutions to climate change, problem solving, and critical thinking | “Identify challenges and seek system-based solutions through dialogue and collaboration, establishing and respecting commitments” | S26 |

| 7 | systems-thinking | explicit mention of a “systems*” thinking OR approach | “applies a systems thinking and understanding” | S23 |

Thematic findings on the knowledge and skills identified in the syllabi (Table 5 in full thesis)

Pedagogy for Transformation

Deductively coding syllabi (n=156) for pedagogy showed mixed approaches for how declarative, affective, and procedural knowledges are taught. I found there is a greater opportunity for more intentional place-based learning or service learning that can support host communities with climate adaptation and mitigation practices in support of emission reductions. The deductively coded pedagogical findings varied across the syllabi and less than 50% of the syllabi included information on the pedagogical approaches for the three knowledge types. Further, less than 30% of syllabi linked learning outcomes with the pedagogical approaches. Of the n=49 syllabi that included pedagogy, the most common pedagogical approaches for declarative knowledge were lecture, essay/paper, quiz/test/exam. The most common pedagogical approach for affective knowledge was through reflection/reflexive exercises. Lastly, the most common pedagogical approach for procedural knowledge was through place-based learning or service learning.

| Knowledge Type | Pedagogical Approach | Examples in Syllabi | Referenced Syllabus |

| declarative (factual) pedagogy | “This seminar focuses on the analysis and use of climate models in understanding and projecting climate change in the future.” | S187 |

| “The course will integrate course lectures and readings with group discussions and interactive excursions outside the classroom in order to thoroughly interrogate course topics” | S219 | ||

| affective (feelings) pedagogy | “Promote empathy, self-reflection, and critical thinking as complementary and mutually reinforcing learning skills” | S198 |

| “The purpose is to ask the students to reflect on their own positionality and make them aware of the ways positionality shapes the research question, relation with the research participants, approach in data collection, data processing, and the representation of research participants in the final project.” | S189 | ||

| procedural (actions) pedagogy | “Students will analyze carbon footprints at three scales, create carbon scenarios for all scales, and determine the most efficient level of implementation.” | S187 |

| “Aboriginal culture was a spoken culture of stories, and so students’ learning is based on the principles of close observation, discussions, and firsthand experience, in order to acquire a better understanding of the First Australians’ intimate understanding of ecology, environmental management, and Aboriginal cultural conservation and restoration.” | S176 |

Example excerpts of syllabi deductively coded for pedagogical approaches (Table 6 in full thesis)

Educational reform should emphasize climate literacy that centers on personal responsibility for climate action and effectively teach feelings knowledge and action knowledge—for how to reduce carbon emissions.

International Climate Educators Perspective

Climate educators believe courses should include holistic approaches to teaching climate education, but there is a mismatch between what international climate educators believe should be taught and what is taught in practice. Educators agree with “account budget thinking” “I do climate action in other aspects of my life to account for the travel emissions of students taking X course” and through “habituation” “I feel travel is so deeply ingrained in the practice of the program and therefore hard to change” (Wolrath Söderberg & Wormbs 2019). Further, international climate educators favor collective action over individual action for emission reductions.

Overcoming this knowledge-to-action gap requires new ways of understanding the dilemma and disrupting business-as-usual behaviors and norms.

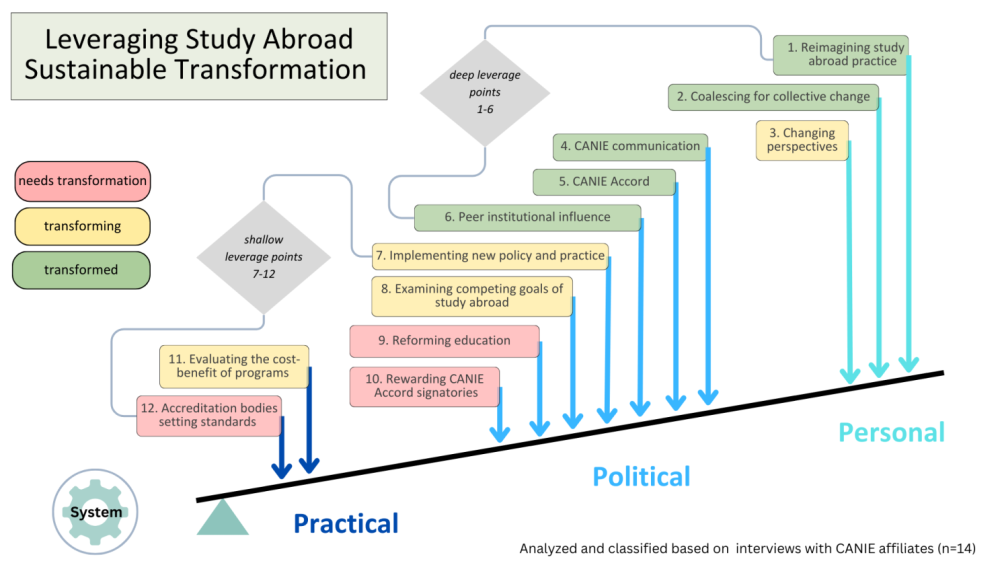

The Climate Action Network for International Educators leverages transformation through knowledge dissemination on climate action, providing study-abroad affiliates with practical emission reduction pathways. Namely through, the CANIE accord—a roadmap of 70 climate actions international education programs and affiliates can take.

Future Directions

My study supports research in sustainability transitions and climate education. Further research could dig into the numbers of how CANIE influences emission reductions and if and how students reduce emissions after taking international climate education courses. Including students in this conversation would help provide a more holistic perspective on international education for systems change in alignment with sustainable futures.

Please reach out if you have additional insights or questions: Julia Roellke jroellke@gmail.com or are interested in getting involved with the Climate Action Network for International Educators. This is a brief overview of high-level takeaways from my thesis and you can find a link to my full study here.

References

Campbell, A. C., Nguyen, T., & Stewart, M. (2023). Promoting International Student Mobility for Sustainability? Navigating Conflicting Realities and Emotions of International Educators. Journal of Studies in International Education, 27(4), 621–637. https://doi.org/10.1177/10283153221121386

Feldbacher, E., Waberer, M., Campostrini, L., & Weigelhofer, G. (2023). Identifying gaps in climate change education—A case study in Austrian schools. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2023.2214042

Fraude, C., Bruhn, T., Stasiak, D., Wamsler, C., Mar, K., Schäpke, N., Schroeder, H., & Lawrence, M. (2021). Creating space for reflection and dialogue: Examples of new modes of communication for empowering climate action. GAIA – Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 30(3), 174–180. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.30.3.9

Frick, M., Neu, L., Liebhaber, N., Sperner-Unterweger, B., Stötter, J., Keller, L., & Hüfner, K. (2021). Why Do We Harm the Environment or Our Personal Health despite Better Knowledge? The Knowledge Action Gap in Healthy and Climate-Friendly Behavior. Sustainability, 13(23), Article 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313361

Hale, B. W. (2019). Wisdom for Traveling Far: Making Educational Travel Sustainable. Sustainability, 11(11), 3048. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113048

Hindley, A. (2022). Understanding the Gap between University Ambitions to Teach and Deliver Climate Change Education. Sustainability, 14(21), Article 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113823

Islam, Md. A., Haji Mat Said, S. B., Umarlebbe, J. H., Sobhani, F. A., & Afrin, S. (2022). Conceptualization of head-heart-hands model for developing an effective 21st century teacher. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 968723. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.968723

Kates, R. W., Clark, W. C., Corell, R., Hall, J. M., Jaeger, C. C., Lowe, I., McCarthy, J. J., Schellnhuber, H. J., Bolin, B., Dickson, N. M., Faucheux, S., Gallopin, G. C., Grübler, A., Huntley, B., Jäger, J., Jodha, N. S., Kasperson, R. E., Mabogunje, A., Matson, P., … Svedin, U. (2001). Sustainability Science. Science, 292(5517), 641–642.

Knutti, R. (2019). Closing the Knowledge-Action Gap in Climate Change. One Earth, 1(1), 21–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2019.09.001

Kranz, J., Schwichow, M., Breitenmoser, P., & Niebert, K. (2022). The (Un)political Perspective on Climate Change in Education—A Systematic Review. Sustainability, 14(7), Article 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074194

Landon, A. C., Woosnam, K. M., Keith, S. J., Tarrant, M. A., Rubin, D. M., & Ling, S. T. (2019). Understanding and modifying beliefs about climate change through educational travel. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(3), 292–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1560452

Leichenko, R., Gram-Hanssen, I., & O’Brien, K. (2022). Teaching the “how” of transformation. Sustainability Science, 17(2), 573–584. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-021-00964-5

Leichenko, R., & O’Brien, K. (2020). Teaching climate change in the Anthropocene: An integrative approach. Anthropocene, 30, 100241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ancene.2020.100241

Nicholas, K. (2021). Under the sky we make: How to be human in a warming world. G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Shields, R. (2019). The sustainability of international higher education: Student mobility and global climate change. Journal of Cleaner Production, 217, 594–602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.291

Stephens, J. C., Frumhoff, P. C., & Yona, L. (2018). The role of college and university faculty in the fossil fuel divestment movement. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene, 6, 41. https://doi.org/10.1525/elementa.297

Tan, D. Y., Tay, E. G., Teo, K. M., & Shutler, P. M. E. (2021). Hands, Head and Heart (3H) framework for curriculum review: Emergence and nesting phenomena. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 106(2), 189–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-020-10003-2

Woiwode, C., Schäpke, N., Bina, O., Veciana, S., Kunze, I., Parodi, O., Schweizer-Ries, P., & Wamsler, C. (2021). Inner transformation to sustainability as a deep leverage point: Fostering new avenues for change through dialogue and reflection. Sustainability Science, 16(3), 841–858. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00882-y

Wolrath Söderberg, M., & Wormbs, N. (2022). Internal Deliberation Defending Climate-Harmful Behavior. Argumentation, 36(2), 203–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-021-09562-2

Zhang, H., & Gibson, H. J. (2021). Long-Term Impact of Study Abroad on Sustainability-Related Attitudes and Behaviors. Sustainability, 13(4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041953