When teaching my students about climate change, biodiversity loss, plastic pollution or other pressing global sustainability problems, I usually start with the notion of the Anthropocene highlighting that humans have become the main driver of change in the planet’s ecosystems. Then, I introduce the planetary boundaries concept to show that humans are crossing a safe operating space causing irreversible damage to the basic living conditions on Earth.

In this context, I often draw on insights from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the Intergovernmental Platform for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services or refer to the Global Environment Outlook of the United Nations Environment Programme. In this way, I try to ensure that students learn about the current state of environmental degradation. While this approach feels appropriate, I cannot help but wonder: what are students actually taking away from such lessons? And more importantly, am I unintentionally leaving them overwhelmed or disheartened?

Through discussions and readings in the pedagogical course on “Integrating Sustainability Competencies in Curriculum” at the Division for Higher Education Development, I realized how crucial it is for a deeper learning process to more actively engage students and meet them where they are in the overall debate about ecological crisis and the over-exploitation of the planet’s life sustaining resources.

As a result, in a new Master’s level course on Environmental and Planetary Politics at the department of political science, I decided to place strong emphasis on “values-thinking” which I understand, following Redman and Wiek, as a crucial sustainability competence that entails the ability to identify, compare and apply concrete sustainability values and related principles and goals. My key idea was that students develop a deep understanding of their own values in relation to the debate on political responses to human-driven global environmental changes.

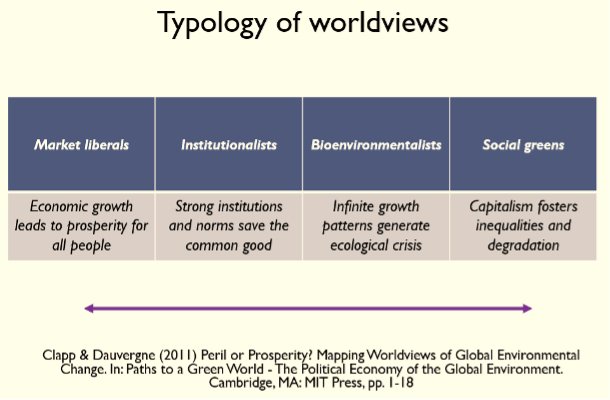

Moreover, I wanted students to realize that the policies of various political actors and institutions are shaped by underlying environmental worldviews. By encouraging students to critically examine different perspectives and position themselves within a renowned typology of worldviews of global environmental change, I aimed to foster a more nuanced understanding of how values influence decision-making processes in addressing sustainability problems.

So how did I do that? After students got familiar with the typology of worldviews distinguishing between market liberals, institutionalists, bioenvironmentalists and social greens, they engaged in partner discussions before positioning themselves in the typology, aligning their own values with the analytical categories of the typology. This exercise did not only deepen their conceptual understanding but also prompted students to critically evaluate their own belief systems and convictions in relation to dominant practices of dealing with environmental problems.

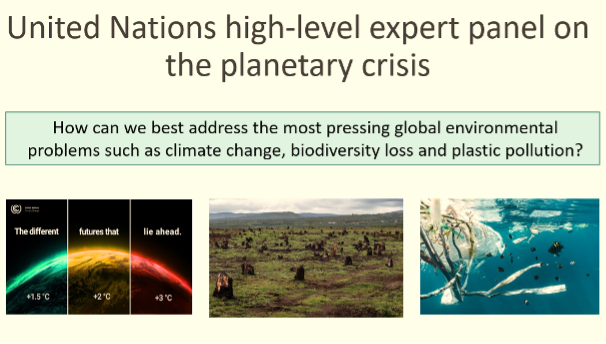

In a next step, students participated in a role-play activity. They were assigned to four groups, each representing one worldview in a “United Nations high-level expert panel”. The groups had the task to provide suggestions based on their respective worldviews how to best respond to pressing global environmental problems such as climate change, biodiversity loss and plastic pollution. That way, students experienced firsthand the strong differences and overlaps between the worldviews and the underlying values.

After the role-play, students reflected on their experiences and shared insights how the role-play shaped their understanding of worldviews. Drawing on these experiences and insights, students used the typology of worldviews as a framework to critically evaluate real-world examples of political responses to sustainability problems, engaging in a debate how different worldviews on global environmental change influence political action.

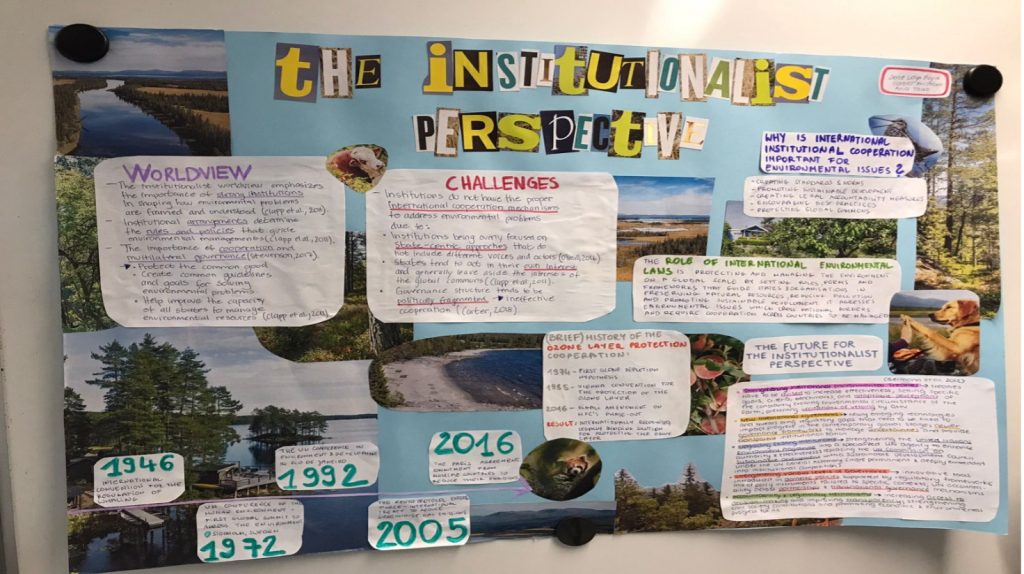

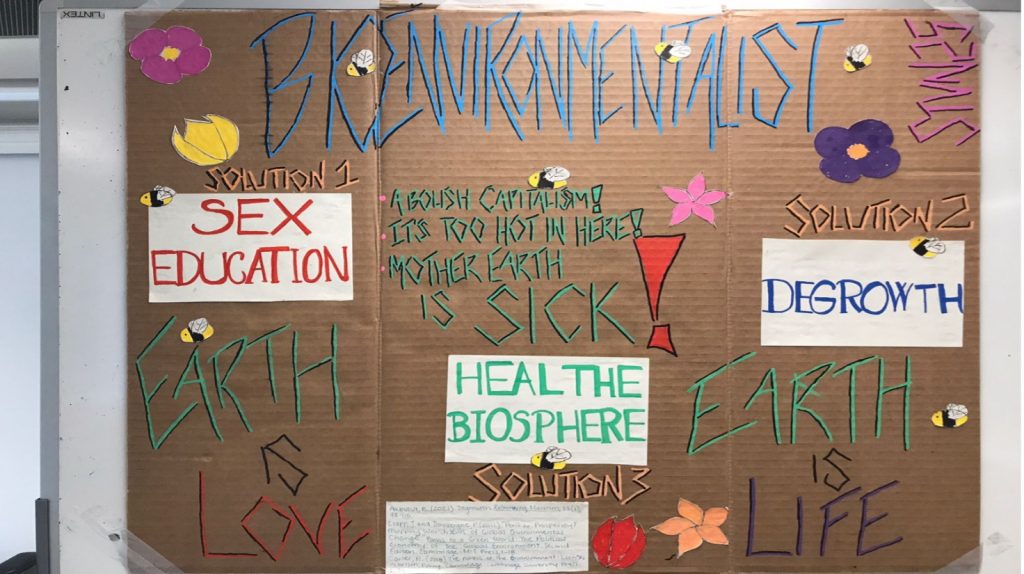

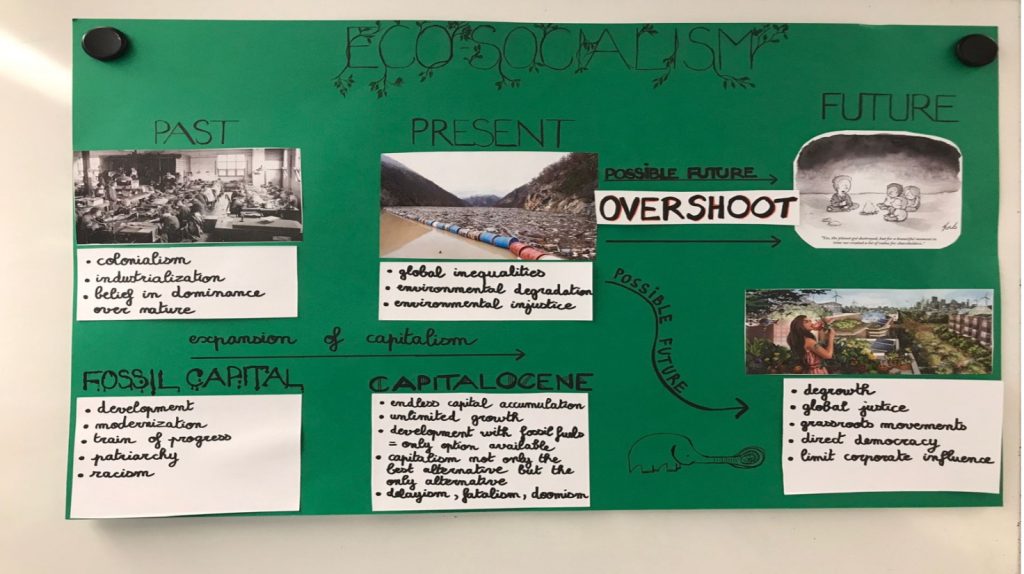

To round this up, students created posters on their different worldviews emphasizing political response strategies for achieving sustainable development in the 21st century. The goal was to give students a chance to be creative and demonstrate their understanding of the connections between values and politics while applying their knowledge in an active environment. These posters were presented and discussed in a concluding exhibition.

In my own reflection, the emphasis on “values-thinking” proved to be highly effective in stimulating student engagement, participation and deep learning. Students actively engaged throughout the course, as they had a chance to connect the thematic input, readings and discussions to their personal beliefs, experiences and ways of thinking. This fostered not only intellectual engagement but also provided a space for students to bring their emotions and personal perspectives into the classroom, enriching the learning experience.

To support students’ deep learning processes, I employed a variety of tools to promote meaningful interactions among students: I started my sessions with “check-ins”, allowing students to express their current emotions and ensuring they felt heard and supported in their respective situations. I conducted a “socio-metric exercise” prior to the role-play to offer opportunities for students to get to know each other, enhancing their ability to work together. I gave students time to reason about critical questions by using the “think-pair-share-technique”, fostering active engagement and peer-to-peer learning. I asked students to compile a “learning journal”, with three guiding questions, encouraging students to document their learning progress.

The ability to identify, compare, and apply concrete sustainability values, principles, and goals is a crucial competence for advancing sustainable development. Combining this competence with future-thinking is particularly promising and essential for generating political and societal changes that disrupt the status quo. With a deep understanding of how values influence political decisions, one can recognize and develop alternative futures that help guide us towards sustainable pathways.

Acknowledgement

I am grateful for the pedagogical support that I received from Steven Curtis, Mirjam Glessmer and Terese Thoni in the pedagogical course Integrating Sustainability Competencies into Curriculum during the autumn term 2024 and greatly appreciated the exchange with all course participants.

References

Clapp, Jennifer, and Peter Dauvergne (2011). Paths to a green world: The political economy of the global environment. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Redman, Aaron, and Arnim Wiek (2021). Competencies for advancing transformations towards sustainability. Frontiers in Education 6, Article 785163.

Warburton, Kevin (2003). Deep learning and education for sustainability. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 4(1), 44-56.