There were six presentations related to teaching sustainability at LTH’s 13th pedagogical inspiration conference in December 2025, that’s a new record! Here are summaries based on the articles published in the conference proceedings (which are all linked below).

Synergies between multi-level strategies to better prepare our students for a highly uncertain future (Björnsson et al., 2025)

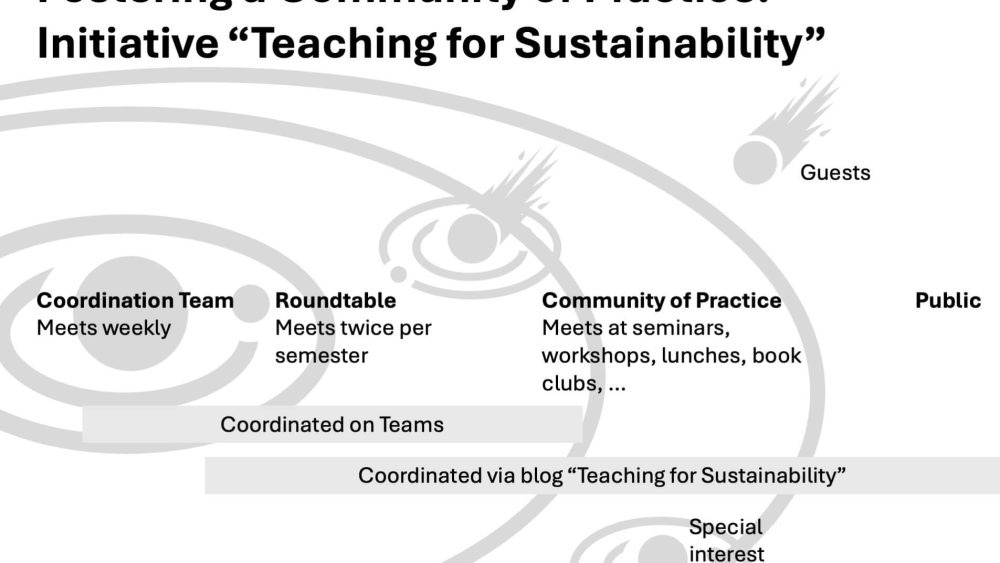

In this paper (which I am a co-author on), we discuss how grassroot initiatives by teachers including sustainability in their own courses can be supported by “middle-out” initiatives, like our initiative Teaching for Sustainability or collegial project courses, and top-down measures like compulsory courses for teachers or students. We ultimately conclude that we need to leverage all of those in combination, but that it is not exactly clear how to do it. The main point of this paper was to establish that there are initiatives on multiple levels and that we are trying to work with them in an integrated way with the goal of preparing our students for a highly uncertain future.

But Terese explores the middle-out perspective aiming to support the bottom-up efforts:

From Workshops to Webinars: Teachers’ Take on Sustainability Training (Thoni, 2025)

Fun anecdote to start: The featured image shows Terese giving her presentation at the conference, and right when she was showing a slide with different global warming scenarios in her motivation, the projector started blinking “TEMPERATURE WARNING”! The colors of the projection weren’t as bad as on this picture though, I think that might have been because of the angle I had relative to the projection…

But now to her paper. From the literature and her work with the initiative Teaching for Sustainability, Terese knows that teachers want to improve their teaching for sustainability, but feel under a lot of (time) pressure, so find it hard to develop the competence and confidence. The goal of Terese’s study is therefore to better understand what kind of materials or events teachers at LU would like to have access to in order to develop their sustainability teaching. She sent out a survey to LU teachers through the network we have built with the initiative and received 37 responses. She finds that teachers are asking mostly for “inspiration such as examples of activities with students, pedagogical courses, and workshops“. Despite time being the most-often mentioned limiting factor to developing teaching for sustainability in our earlier study (Glessmer et al., 2025), shorter formats (like video clips) are not more popular than longer ones, and if time and other resources weren’t limiting, teachers ask for interactive formats, for example workshops. They also suggested they would like to see “student-led formats, meetings with or messages from the University leadership, developing concrete products together as a community, discussing with peers within the subject or teacher team but with external, EfS-expert feedback, and possibility to observe or participate in someone else’s teaching“, and again, if time wasn’t an issue, “more co-teaching, peer feedback and peer communities, as well as retreats to be able to set aside enough time to build strong connections with colleagues and co-create“. And someone even suggested a physical meeting space for the community! Terese concludes that “educators have an important role to play in building a sustainable future and it is important that the university supports and empowers them in ways that they find meaningful“, and I could not agree more!

Since “inspiration” was such a popular choice (and actually also the only option where nobody responded that it was not useful or that they did not know), here is some inspiration that Sara and Max presented right after.

Integrating sustainability competencies into electrical engineering courses (Willhammar and Collins, 2025)

Sara and Max investigate how sustainability competences can be meaningfully embedded in two electrical engineering courses that they are teaching. They conducted four interviews with their peers to identify current practices and challenges and find that sustainability is often implicit, focussed on environmental impact, or added on in stand-alone workshops on for example ethics. They also write that “[t]he interviewed teachers expressed an awareness of its importance and a willingness to do more, but noted that, currently, integration depends largely on individual efforts rather than a coordinated departmental or program-level approach” and that “[t]he main challenges identified were related to uncertainty about how to meaningfully integrate sustainability into technically demanding courses. Time limitations and already dense course designs were seen as barriers to introducing new material without sacrificing already existing content. Some teachers also expressed uncertainty about “what sustainability in teaching” actually entails – whether it only focuses on content (e.g., renewable energy, efficiency) or on (and if that case, how) developing competencies such as systems thinking, ethical reasoning, and long-term perspectives. Lack of coordinated support and shared understanding across courses and programmes further complicates integration” — interesting results to note for my future work with the initiative Teaching for Sustainability!

They then suggest several ways of integrating sustainability in a meaningful way, for example starting project descriptions from a sustainability motivation, making already addressed sustainability competencies (for example systems thinking) explicit as such, creating opportunities for co-creation with students, and starting and ending a course with discussion seminars, highlighting sustainability relevance of the subject. Their paper concludes with the (unfortunately due to the page limit highly condensed, but nevertheless super helpful) learning outcomes that they have developed for their courses, teaching and learning activities that address those learning outcomes, and concrete implementation examples for both courses. One example that I loved was “[s]tudents and teachers from two different disciplines, together explore interdisciplinary trade-offs. Exercises during lecture breaks encourages the students to “see the world” through the three lenses. In an individual reflection task in the end they are to reflect on trade-offs“, and I cannot wait to hear about Sara and Max’s experiences when they actually implement all those ideas this year (2026)!

Another inspirational example was investigated in aerosol science:

Using wicked problems in teaching for sustainability (Pagels et al., 2025)

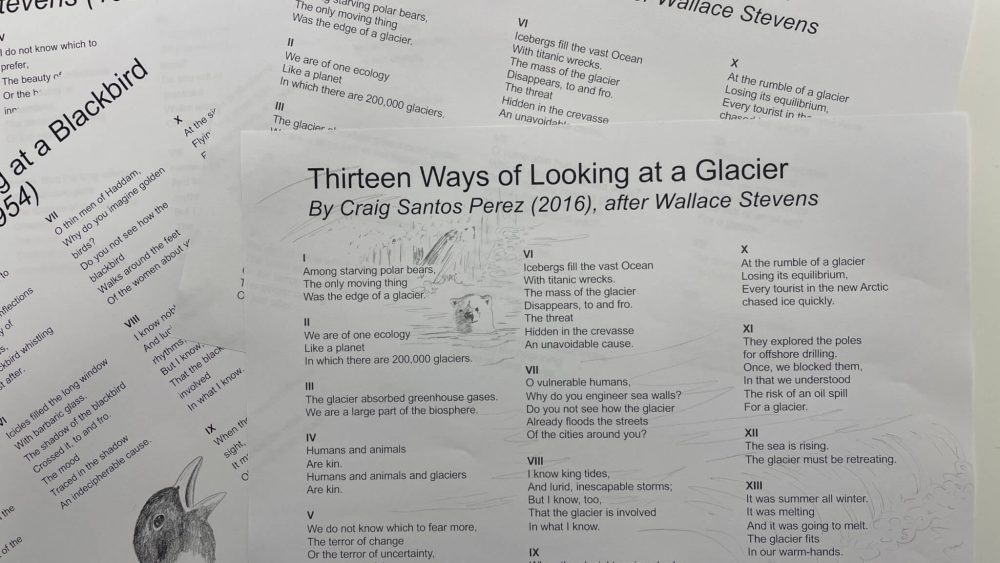

This paper is based on work that started in one of the previous Teaching for Sustainability courses, but that has since developed and tested much more extensively. They took wicked problems in aerosol science that they used as basis for jigsaw-like role plays: Students prepare in groups where each group prepares for later playing a specific stakeholder, for the role play the groups get mixed so that everybody meets all the other stakeholders, and the whole is rounded off with a whole-class debriefing and discussion of the experience. What I really liked was that students could pick their roles and to some extent even come up with their own!

In their evaluation, the authors find that students are generally very positive about the experience (especially when it is done a second time, so they have a better understanding of how things will go). They write that “[s]ome students pointed out that so far throughout their education they learned to argument for the environmental consequences, but it was one of the first times when they had to consider economic, political, social, and private emotionally loaded perspectives. They considered it thought-provoking and valuable“. The “private emotionally loaded perspectives” refer to “parents whose children suffer from respiratory diseases“, which I think is also a great idea to include! The authors will now make attendance of these sessions mandatory in the future. For the pilot they were not mandatory, but it was a smart move to already now include exam questions formulated as wicked problems to stress the importance of looking at a problem from several perspectives (which, based on the exam results, most students seem to have learned).

Staying with wicked problems, in a project that I only heard and read about but wasn’t otherwise involved with at all (in contrast to the others in this blog post):

Teaching sustainability- workshops – bridging real-world challenges from different systemic levels (Krautscheid et al., 2025)

The authors designed three workshops on three sustainability challenges that address individual, organizational, and systemic levels, and tested them in different educational settings as well as in-person and online. They scaffolded interaction, preparing participants, through easy warm-ups on Menti, for the interactive core activities. There, participants first envision the sustainable behaviour in a given context, then identify barriers which might hinder that behaviour being enacted, and finally propose solutions to overcome those barriers. I really like this approach and hope that the authors will share their materials on our Teaching Sustainability blog in the near future!

The next paper is a conceptual one:

Transgressive learning in sustainability pedagogy: promises, risks, and responsible integration (Lasselin, Haldar, and Iao-Jörgensen, 2025)

Clément, Stuti and Jenny are exploring transgressive learning. They write that transgression “can be seen as a way of translating critical thinking and putting knowledge into action for sustainability“, but it comes with risks, for example students putting their learning into action and then being punished for pushing against norms, or the actions not being constructive or well thought through (but then who decides?). This paradox between universities on the one hand being very traditional and hierarchical, but then teaching how to work against norms, is an interesting challenge that they apply to sustainability teaching. For that, they sent out a survey and found that 2/3rds of the respondents “agree or strongly agree that challenging dominant norms is essential to advance sustainability“, while 1/4th “viewed encouraging students to challenge dominant norms negatively“.

So how could it be done responsibly? Clément, Stuti and Jenny suggest six competencies that students need to learn to engage with transgression in a responsible way:

- Assessing the sustainability of norms

- Acknowledging the possibility of transgression and identifying the different types of transgression

- Identifying several transformative pathways

- Evaluating and comparing transgression impacts across scales

- Identifying and adapting to uncertainties

- Practicing transgression responsibly

They then discuss how to approach this as a teacher, and highlight among others the need to “accept co-learning situations” where the teacher positions themself as a co-learner, being cautious, but also acting as role model: “teaching transgression competencies may even require the teacher to apply such competencies very directly, as the teacher may encounter resistance from other teachers and educational institutions to the idea that they are teaching transgression“.

The paper ends here, but in their conference presentation about a month after the paper was due, they already had inspiring results from when they tested these ideas in teaching; gotta love the engagement! But this will be published in another paper currently under preparation, so I won’t spoil anything here.

So this is for explicitly teaching-sustainability focussed presentations at that conference! Now what are we planning for LUTL 2026?

Björnsson, I., Niklewski, J., Glessmer, M. S., Janson, U., Thoni, T., Modig, K. (2025). Synergies between multi-level strategies to better prepare our students for a highly uncertain future. In: Proceedings of LTH:s 13:e Pedagogiska Inspirationskonferens, 4 december 2025. https://www.lth.se/fileadmin/cee/genombrottet/konferens2025/E3_Bjornsson_etal.pdf

Carling, L. (2023). Studentperspektiv på hållbarhetsundervisningen: kopplingar mellan yrkesroll och hållbarhetsarbete – en pilotstudie. In: Proceedings of LTH:s 13:e Pedagogiska Inspirationskonferens, 7 december 2023. https://www.lth.se/fileadmin/cee/genombrottet/konferens2023/B2_Carling.pdf

Krautscheid, L., Pugh, R., Wadin, J., and Kristav, P. (2025). Teaching sustainability- workshops – bridging real-world challenges from different systemic levels. In: Proceedings of LTH:s 13:e Pedagogiska Inspirationskonferens, 4 december 2025. https://www.lth.se/fileadmin/cee/genombrottet/konferens2025/E4_Krautscheid_etal.pdf

Lasselin, C., Haldar, S., and Iao-Jörgensen, J. (2025). Transgressive learning in sustainability pedagogy: promises, risks, and responsible integration. In: Proceedings of LTH:s 13:e Pedagogiska Inspirationskonferens, 4 december 2025. https://www.lth.se/fileadmin/cee/genombrottet/konferens2025/D4a_Lasselin_etal.pdf

Pagels, J., Rissler, J., Friberg, J., and Wierzbicka, A. (2025). Using wicked problems in teaching for sustainability. In: Proceedings of LTH:s 13:e Pedagogiska Inspirationskonferens, 4 december 2025. https://www.lth.se/fileadmin/cee/genombrottet/konferens2025/F1_Pagels_etal.pdf

Thoni, T. (2025). From Workshops to Webinars: Teachers’ Take on Sustainability Training. In: Proceedings of LTH:s 13:e Pedagogiska Inspirationskonferens, 4 december 2025. https://www.lth.se/fileadmin/cee/genombrottet/konferens2025/D4b_Thoni.pdf

Willhammar, S., and Collins, M. (2025). Integrating sustainability competencies into electrical engineering courses. In: Proceedings of LTH:s 13:e Pedagogiska Inspirationskonferens, 4 december 2025. https://www.lth.se/fileadmin/cee/genombrottet/konferens2025/D4c_Willhammar_Collins.pdf

Comments