Publicerad av Aftonbladet 7/2 2025:

163 universitetsanställda ställer sig bakom studenters krav att påskynda förändringen av högre utbildning så att studenterna som medborgare och i sina framtida yrkesliv ska kunna bidra till en samhällsomställning för hållbarhet. Dessa krav har studenterna tidigare uttryckt i ett öppet brev till rektorerna vid samtliga svenska lärosäten och de inkluderar bland annat tvärdisciplinära utbildningar och ökat studentinflytande för att skapa en hållbar samhällsomställning.

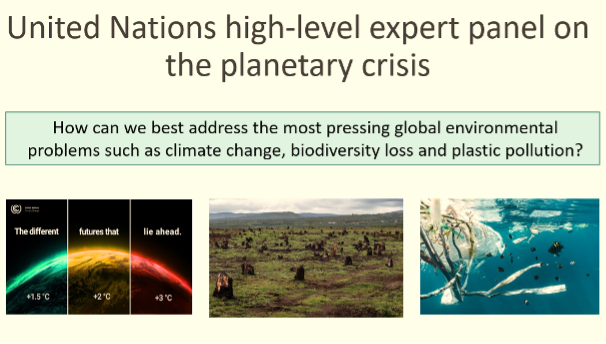

Medan alltmer alarmerande forskningsresultat visar att mänskligheten står inför en existentiell kris på grund av klimatförändringar, förlust av biologisk mångfald och överskridandet av ytterligare planetära gränser så sker mycket arbete vid svenska universitet och högskolor fortfarande som om dessa kriser inte existerade. Det gäller inte minst undervisningen. I ett öppet brev skickar representanter för 13 olika studentkårer en uppmaning till landets rektorer att påskynda processen att göra utbildningen mer relevant, en uppmaning som vi forskare och lärare vid universitetet och högskolor ställer oss helhjärtat bakom.

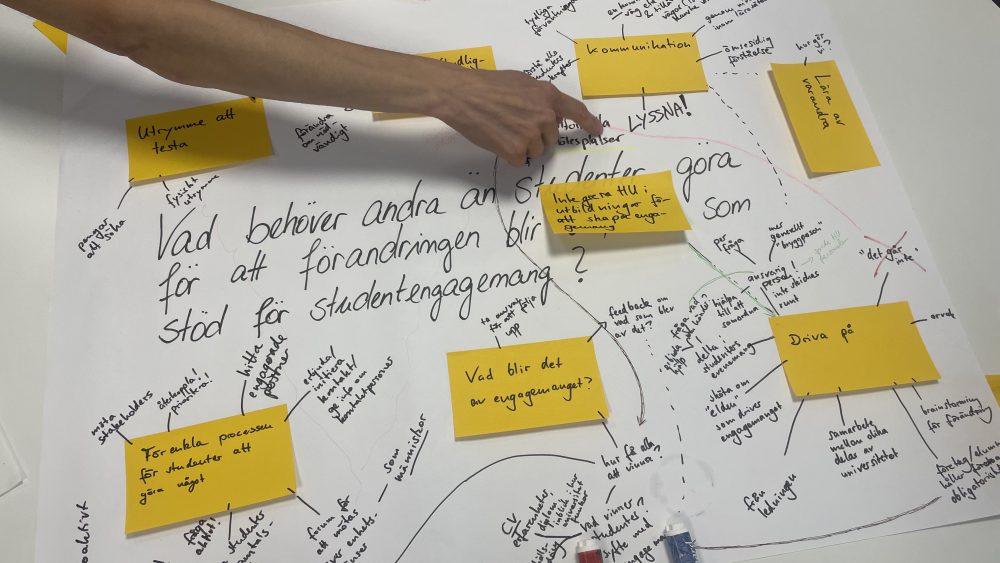

Brevet är resultatet av en workshop som genomfördes i oktober 2024, där representanter för studentkårerna och Klimatnätverkets arbetsgrupp för lärande för hållbar utveckling diskuterade hur universitetens utbildningar behöver förändras för att bättre förbereda studenterna för att vara en aktiv och kunnig del av den samhällsomställning som krävs för en hållbar och rättvis framtid.

Klimatnätverket är ett nationellt nätverk av universitet och högskolor som bland annat syftar till att stärka samarbetet och utbytet mellan lärosätena inom klimatområdet och underlätta för lärosätena att uppfylla sin del av Parisavtalet. Klimatnätverkets arbete bedrivs i olika fokusgrupper varav en är lärande för hållbar utveckling.

De allvarliga och omfattande brister som studenterna identifierade i dagens utbildningssystem är:

- att det saknas förståelse och acceptans för att utbildningarna behöver förändras i grunden om de ska kunna utbilda studenter att bidra till en hållbar värld. Därmed saknas också vilja och beslutsamhet till sådan förändring.

- att akademin, som står som garant för mycket av kunskapen kring klimat- och miljöutmaningarna, inte fullt ut är med och driver samhällsomställningen.

- att alla utbildningar inte lyfter frågor om hållbarhet och dess komplexitet eller karaktäriseras av lärande för hållbar utveckling, samt att det saknas progression i lärandet för hållbar utveckling.

Studenterna kräver att utbildningarna förändras på följande sätt:

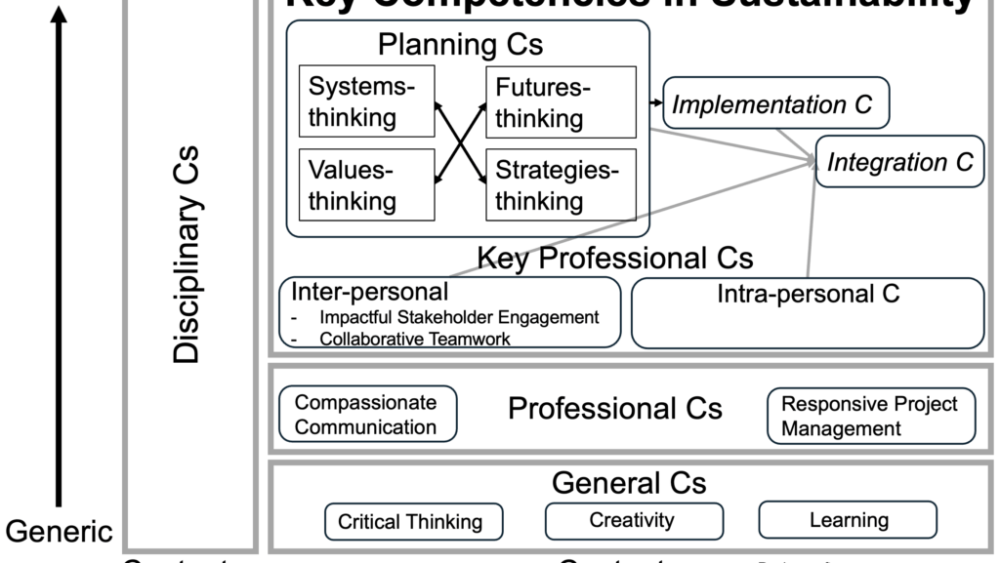

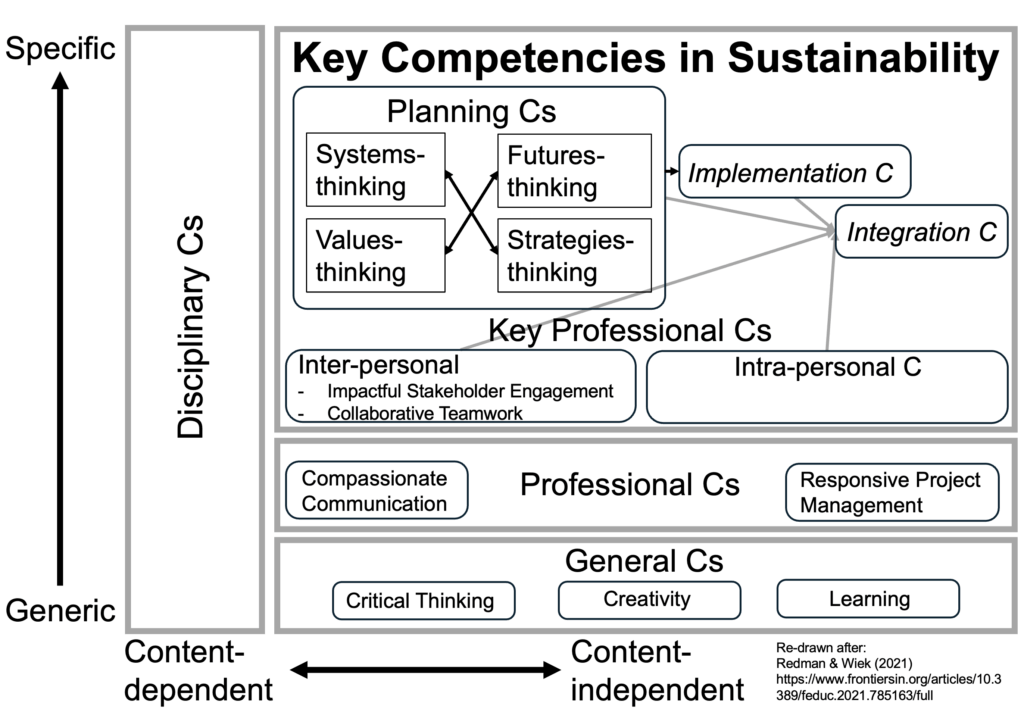

- att utbildningar designas, både med avseende på innehåll och pedagogik, med utgångspunkt i de hållbarhetsutmaningar som världen står inför, så att studenternas kompetenser därigenom är aktuella och relevanta för samhällets hållbarhetsutmaningar.

- att utbildningar inkluderar tvärdisciplinära möten och kurser där studenter får arbeta med lösningar till verkliga uppdragsgivare och deras samhällsutmaningar.

- att alla lärare och personer i ledande roller på våra lärosäten får kompetens om lärande för hållbar utveckling och om lärosätenas ansvar och möjligheter att bidra till samhällsomställning genom lärande för hållbar utveckling.

Studenterna anser att de har en central roll i det förändringsarbetet och att deras initiativ och engagemang måste tas på allvar. De uttrycker i brevet att deras röster ibland inte får gehör. De uttrycker att det är avgörande att:

- lärosätena i större grad efterfrågar och tar tillvara studenternas kompetens i utformningen och genomförandet av de förändringar av kurser och utbildningsprogram som behövs,

- studenternas röster tas på allvar i informella och formella sammanhang och att studentinflytande meriteras som en del av utbildningarna,

- Sveriges lärosäten gemensamt etablerar ett Forum för transformation av högre utbildning för ett större ansvarstagande för framtiden där både studenter, lärare, utbildningsforskare och universitetsledningar finns representerade.

Vi håller med studenterna och tycker att det är viktigt att tillmötesgå deras krav. Vi uppmanar er som rektorer att påskynda denna förändringsprocess, så att de kunskaper och färdigheter som studenterna får med sig från våra lärosäten förbereder dem väl för deras framtida yrkesroller, inklusive att ge dem verktyg och möjlighet att aktivt bidra till en hållbar samhällsomställning. Ett nära samarbete mellan alla svenska högskolor och universitet, studenter och relevanta samhällsaktörer är avgörande för att lyckas med denna omställning. Vi som undertecknar denna text är beredda att bidra till denna förändring men behöver också ett helhjärtat stöd från ledningarna vid de högskolor och universitet där vi är verksamma för att lyckas.

Jeannette Eggers, forskare i skoglig planering, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet

Glenn Bark, universitetslektor i malmgeologi, Luleå tekniska universitet

Esther Hauer, universitetslektor i pedagogik i arbetslivet, Uppsala universitet

Karin Gerhardt, forskare i biologisk mångfald, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet

Anne-Kathrin Peters, docent i teknikvetenskapens lärande, KTH

Ben Kenward, universitetslektor i psykologi, Uppsala universitet

Isabelle Letellier, universitetslektor i barn och ungdomsvetenskap, Stockholm universitet

Sverker Molander, professor i miljösystem och risk, Chalmers Tekniska Högskola

Maria Hylberg, doktorand, Barn- och ungdomsvetenskapliga institutionen, Stockholms universitet

Cecilia Enberg, universitetslektor, Linköpings universitet

Malin Östman, kurssamordnare, CEMUS, Uppsala universitet

Ulrika Persson-Fischier, PhD, Excellent lärare, adjunkt, Uppsala universitet

Johanna Nygren Spanne, civ.ing, adjunkt, programansvarig för Miljövetarprogrammet – Människa, Miljö, Samhälle, Malmö universitet

Fredrika Mårtensson, Människa och samhälle, universitetslektor, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet

Hannu Larsson, universitetslektor i informatik, Örebro universitet

Diana Holmqvist, universitetslektor i pedagogik och vuxnas lärande, Linköpings universitet

Johanna Björklund, universitetslektor i miljövetenskap, Örebro universitet

Ewa Livmar, Kurssamordnare, CEMUS, Uppsala universitet

Helena Fornstedt, postdoktor med undervisningsansvar, Uppsala universitet

Carin Cuadra, professor i socialt arbete, Malmö universitet

Mirjam Glessmer, universitetslektor och pedagogisk utvecklare, Lunds Universitet

Felix-Sebastian Koch, docent, Linköpings Universitet

Emilia Åkesson, fil. dr pedagogik, postdoktor i genusvetenskap, Umeå Universitet

Max Koch, professor i socialpolitik och hållbarhet, Lunds universitet

Jayeon Lee, universitetslektor i socialt arbete, Göteborgs universitet

Naghmeh Nasiritousi, docent, Linköpings universitet

Lena Sawyer, docent i socialt arbete, Göteborgs universitet

Stephanie Rost, doktorand, Göteborgs universitet

Klara Bolander Laksov, professor, Stockholms universitet

Anders Rosén, universitetslektor i ingenjörsutbildning, KTH

Per Andersson, professor i pedagogik, Linköpings universitet

Cecilia Josefsson, doktorand och universitetslärare, Uppsala universitet

Marie Kvarnström, konsulent, SLU Centrum för biologisk mångfald

Charlotte Ponzelar, doktorand i didaktik, Uppsala universitet

Natalie Jellinek, pedagogisk utvecklare, Undervisning och Lärande, Karolinska Institutet

Rhiannon Pugh, universitetslektor i innovation, Lunds universitet

Matilda Karlsson, doktorand i socialt arbete, Göteborgs universitet

Christoffer S. Kanarp, forskare i miljökommunikation, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet

Anna-Lena Sahlberg, universitetslektor i fysik, Lunds universitet

Cecilia Lalander, docent i teknologi, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet

Charlotta Delin, pedagogisk utvecklare, KTH

Johanna Spångberg, forskare hållbar livsmedelsproduktion, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet

Martina Angela Caretta, universitetslektor och docent inom kulturgeografi, Lunds universitet

Iann Lundegård universitetslektor och docent i nv-ämnenas didaktik Stockholms universitet

Fredrik Björk, adjunkt i miljövetenskap och doktorand i miljöhistoria, Malmö universitet

Manuel Fernández Santana, doktorand, Linköpings universitet

Susanna Sternberg Lewerin, professor i epizootologi & smittskydd, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet

Kajsa Emilsson, forskare i socialpolitik och hållbarhet, Lunds universitet

Sara Gabrielsson, universitetslektor i hållbarhetsvetenskap, Lunds universitet

Helena Röcklinsberg, docent i etik, universitetslektor i djuretik, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet

Jana Weiss, docent i miljökemi, Stockholms universitet

Brita Sundelin, docent i miljövetenskap, Stockholms universitet

Nike Lindhe, doktorand i klinisk psykologi, Linköpings universitet

Hulda Karlsson-Larsson, doktorand i psykologi, Linköpings universitet

Ola Uhrqvist, universitetslektor, Linköpings universitet

Carole Chappuis, doktorand i naturvetenskapernas didaktik, Linköpings universitet

Joëlle Rüegg, professor i miljötoxikologi, Uppsala universitet

Johanna Lundström, forskare i skoglig planering, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet

Arthur Rohaert, doktorand i brandteknik, Lunds universitet

Susanne Antell, universitetsadjunkt i naturvetenskap, Högskolan Dalarna

Ingrid Strid, forskare och lärare vid Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet, Uppsala

Tullia Jack, biträdande lektor, docent, Tjänstevetenskap, Lunds Universitet

Felicia Garcia, pedagogisk utvecklare, Högskolepedagogiskt centrum, Örebro universitet

Muriel Côte, universitetslektor och docent inom kulturgeografi, Lunds universitet

Katarina Andreasen, docent i biologi, Uppsala universitet

Agnes Hamberger, doktorand i utbildningssociologi, Uppsala universitet

Elenor Kaminsky, universitetslektor, docent i Folkhälsa vid Uppsala universitet

Eva Friman, forskare & programchef, Centrum för hälsa och hållbarhet, Uppsala universitet

Jessika Richter, biträdande universitetslektor i hållbar konsumtion, Lunds universitet

Yulia Vakulenko, universitetsadjunkt i förpackningslogistik, Lunds universitet

Åke Hestner, universitetsadjunkt i Matematikdidaktik, Högskolan Dalarna

Karin Steen, universitetslektor, Centrum för studier av uthållig samhällsutveckling/LUCSUS och pedagogisk utvecklare, Avdelningen för högskolepedagogisk utveckling, Lunds Universitet

Anton Grenholm, samordnare för miljö- och hållbarhetsfrågor, Högskolan Dalarna

Thomas Hickmann, biträdande universitetslektor i statsvetenskap, Lunds universitet

Rolf Larsson, professor i tillämpad matematik och statistik, Uppsala Universitet

Björn Victor, professor i datalogi, Uppsala universitet

Ronny Alexandersson, doktor i biologi, Uppsala universitet

Frederik Aagaard Hagemann, doktorand inom urban landskapsplanering, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet

Kathrin Zeller, docent och universitetslektor i immunteknologi, Lunds Universitet

Ida Wallin, forskare och lärare, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet

Kevin Noone, professor emeritus i kemisk meteorologi, Stockholms universitet

Magdalena Malm, forskare inom proteinvetenskap, KTH

Anna Malmquist, docent i psykologi, Linköpings universitet

Kristina Boréus, professor i statskunskap, Uppsala universitet

Romina Martin, forskare och lärare i hållbarhet, Stockholm Universitet

Stephanie Carleklev, universitetslektor i design, Linnéuniversitetet

Caroline Greiser, forskare och lärare i landskapsekologi, Stockholm universitet

Patrik Andersson, professor i miljökemi, Umeå universitet

Eva-Maria Nordström, universitetslektor i skoglig planering, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet

Veronica Flodin, universitetslektor i naturvetenskapernas didaktik, Stockholms universitet

Martin Hultman, docent i vetenskaps-, teknik och miljöstudier, Chalmers Tekniska Högskola

Sachiko Ishihara, doktorand i kulturgeografi, Uppsala universitet

Patrik Oskarsson, docent i landsbygdsutveckling, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet, Uppsala

Johanna Lönngren, docent i teknikdidaktik, Umeå universitet

Per Adman, docent och universitetslektor, Uppsala universitet

Tomas Persson, docent i matematik, Lunds tekniska högskola, Lunds universitet

Marie Bengtsson, professor i kemi med inriktning mot kemisk ekologi, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet

Ebba Malmqvist, docent i miljömedicin, Lunds universitet

Anna Scaini, forskare och lärare i vattenresurser, Stockholms universitet

Cecilia Sundberg, universitetslektor i bioenergisystem, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet

Juan Samper, doktorand i hållbarhetsvetenskap, Lunds universitet

Stefano Manzoni, professor i ekohydrologi, Stockholms universitet

Göran Finnveden, professor i miljöstrategisk analys, KTH

Hanna Grauers Wiktorin, postdoktor, Uppsala Universitet

Göran Bolin, professor i medie- och kommunikationsvetenskap, Södertörns högskola

Michael Gilek, professor i miljövetenskap, Södertörns högskola

Kristina Riegert, professor i journalistik, Södertörns högskola

Maria Wolrath Söderberg, docent i retorik, Södertörns högskola

Daniel Pargman, docent i medieteknik med inriktning mot hållbarhet, KTH

Jonas Andersson, docent i medie- och kommunikationsvetenskap, Södertörns högskola

Maria Niemi, docent i folkhälsovetenskap, Karolinska Institutet

Isabel Löfgren, lektor i medie- och kommunikationsvetenskap, Södertörns högskola

Klas Ytterbrink Nordenskiöld, doktorand i medicin, Karolinska Institutet

Stina Bengtsson, professor i medie- och kommunikationsvetenskap, Södertörns högskola

Rikard Hjorth Warlenius, docent i samhällsvetenskapliga miljöstudier, Södertörns högskola

Peter Dobers, professor i företagsekonomi, dekan för fakultetsnämnden 2016-2022, Södertörns högskola

Tommy Jensen, professor i företagsekonomi, Stockholms Universitet

Birgitta Schwartz, professor i företagsekonomi, Stockholms Universitet

Marita Cronqvist, docent i pedagogiskt arbete, Högskolan i Borås

Ulf Bergström, docent i marin ekologi, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet

Hervé Corvellec, professor i företagsekonomi, Lunds Universitet

Erik Månsson, universitetslektor, Handelshögskolan vid Karlstads Universitet

Henrik Loodin, fil. dr. sociologi, Lunds universitet

Sara Persson, postdoc i företagsekonomi, Södertörns högskola

Matilda Dahl, docent i företagsekonomi Uppsala universitet

Matilda S. Watz, biträdande universitetslektor i strategisk hållbar utveckling, Blekinge Tekniska Högskola

Åsa Cajander, professor i människa-datorinteraktion, Uppsala universitet

Herman Stål, docent företagsekonomi, Handelshögskolan vid Umeå universitet

Kristin Caravelli-Svärd, doktorand i företagsekonomi, Karlstads Universitet

Helén Williams, docent i miljö- och energisystem, Karlstads universitet

Henrietta Palmer, arkitekt och forskare, Göteborgs Universitet

Göran Broman, professor i maskinteknik, Blekinge Tekniska Högskola

Fredrik Wikström, professor i Miljö- och energisystem, Karlstads universitet

Maria Berge, universitetslektor vid Institutionen för naturvetenskapernas och matematikens didaktik, Umeå universitet

Annette Risberg, gästprofessor i organisation, Malmö Universitet

Markus Schneider, universitetspedagogiska enheten, Karlstads universitet

Michael Håkansson, Lektor i didaktik, Stockholms universitet

Alexis Engström, pedagogisk utvecklare, Mittuniversitetet

Cecilia Åsberg, professor i genus, natur, kultur, The Posthumanities Hub, Linköpings universitet

Sven Borén, Lektor i Strategisk Hållbar Utveckling, Blekinge Tekniska Högskola

Michael Johansson, Forskare Tjänstevetenskap, Lunds universitet

Per Knutsson, lektor i humanekologi, Göteborgs Universitet

Anette Strömberg, universitetslektor innovationsteknik, Mälardalens universitet

Kjell Vowles, postdoktor, Göteborgs universitet.

Cecilia Bratt, lektor i strategisk hållbar utveckling, Blekinge Tekniska Högskola

Annika Olofsdotter Bergström, Lektor Medieteknik, Södertörns Högskola

Nina Wormbs, professor i teknikhistoria, KTH

Adam Wickberg, docent i historiska studier av teknik, vetenskap och miljö, KTH

Alexandra D’Urso, pedagogisk utvecklare på Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet och forskare i pedagogik

Merlina Missimer, docent i Strategisk Hållbar Utveckling, Blekinge Tekniska Högskola

Jenny Helin, docent i företagsekonomi, Rektorsråd för Uppsala universitet Campus Gotland

Annie Gregory, doktorand, Uppsala Universitet

Pernilla Ouis, fil. dr. i humanekologi och professor i socialt arbete vid Högskolan i Halmstad

Lars Hedegård, universitetslektor i företagsekonomi, Högskolan i Borås

Hampus Holmström, analytiker, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet

Dana Bergman, universitetsadjunkt på institutionen för strategisk hållbar utveckling på Blekinge Tekniska Högskola

Birgit Penzenstadler, Associate Professor for Software Engineering, Chalmers Tekniska Högskola and University of Gothenburg

Carl-Gustaf Bornehag, professor i folkhälsovetenskap, Karlstads universitet, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, NY, USA

Malin Knutz, PhD folkhälsovetenskap, Karlstads universitet, programledare för “Hälsa, miljö och samhälle” samt Masterprogrammet i folkhälsovetenskap.

Helena Pedersen, docent i pedagogik, programledare för Masterprogrammet i Education for Sustainable Development, Göteborgs universitet

Carolina Jernbro, docent i folkhälsovetenskap, Karlstads universitet

Åsa Bringsén, lektor i folkhälsovetenskap och programområdesansvarig för Folkhälsovetenskapligt program med inriktning beteendevetenskap, Högskolan Kristianstad.

Ingemar Jönsson, professor i ekologi, Högskolan Kristianstad.

Samuel Petros Sebhatu, universitetslektor, Handelshögskolan vid Karlstads Universitet

Petra Nilsson Lindström, biträdande professor i hälsovetenskap, Högskolan Kristianstad

Lena Gumaelius, docent i teknikvetenskapens lärande, KTH

Comments