Our previous experiences with teaching for, or even about sustainability, is very limited. It has often been something on the periphery, something we knew was important but lacked insights to implement in a meaningful way. The topic of sustainability is something that has come more recently, in a field of education fraught with tradition. We teach courses in structural engineering, a discipline which has experienced few disruptive breakthroughs in recent decades. This has meant that we have become quite comfortable teaching what we learned ourselves when we were students. Meanwhile, the construction sector, accounting for about 21% of the global greenhouse gas emissions [1], is trying to navigate through a green transition. Thus, we don’t know exactly what the construction sector will look like in 10-20 years. One thing is for sure, the sector must become more sustainable. So, while structural engineering as a subject remains unchanged, the boundary conditions for structural engineers are changing in real time. We feel it our duty to equip students for this uncertain future – however, how can we effectively teach sustainability when we ourselves have not been formally educated in this area?

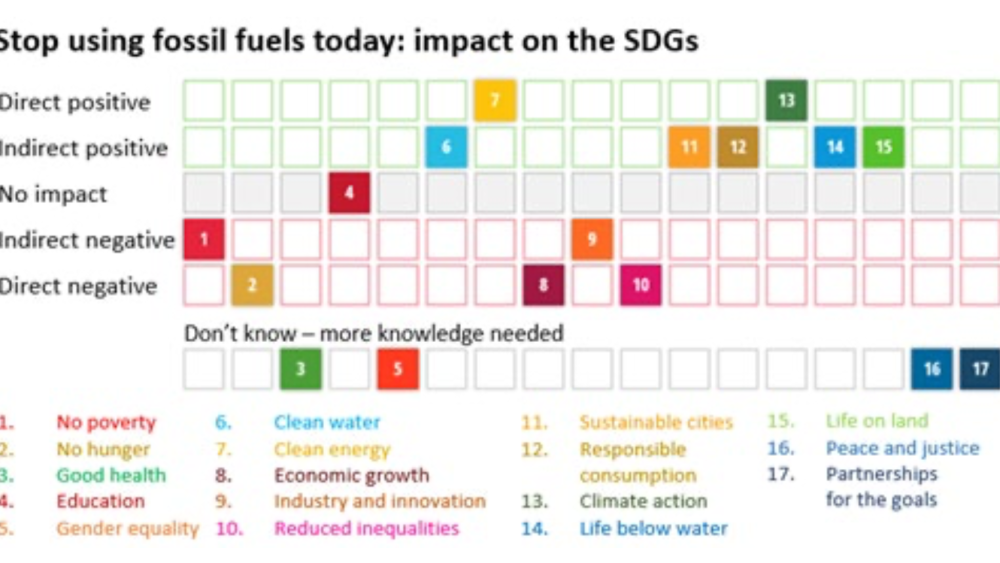

The courses we give at the division of structural engineering all revolve in some way on structures; how they stand, how they fail, how we build them, and how we maintain them. Typical decisions faced by structural engineers include determining the appropriate materials and proper dimensions for a structure such as a building or bridge. These decisions are made considering risk and uncertainty but carry with them potentially high consequences in terms of economic, environmental, as well as social impacts. Historically, these decisions have been made with the ideology of design conservatism. The implicit assumption is that we could increase material consumption (and by extension carbon footprints) as long as our design decisions were on the safe side. This philosophy, however, clashes with the environmentally oriented sustainability goals.

This brief report describes one of our efforts to incorporate sustainability aspects more explicitly into our teaching. As we have limited prior experience with this subject, and given our background as engineers, we have adopted a more careful but practical approach. Thus, although we admit that grander action is required (and especially at curriculum level), we have chosen to focus on one of our courses – a basic course on structural engineering in the second year of the Civil Engineering program (V). Our focus was on incorporating a dedicated two-hour seminar on aspects of sustainability. The aim of the seminar is to actively engage our students, as well as ourselves, in thinking about how the decisions made by structural engineers can affect sustainability and to challenge the traditional ideology of design conservatism. The next section describes in more detail the methodology we used for developing the seminar.

Methodology

To help us in planning the seminar, we utilized three primary methods:

- Short literature review

- Inspirational discussions with more experienced colleagues

- Internal brainstorming sessions

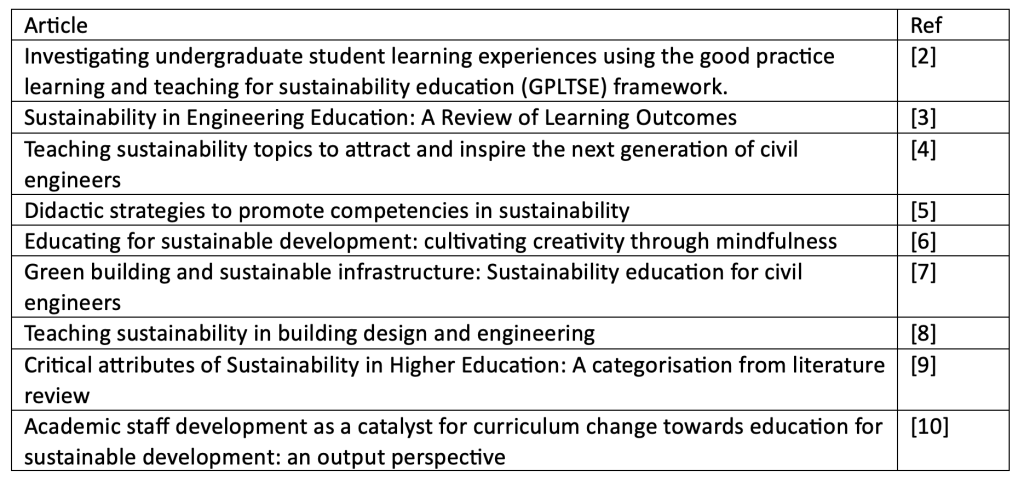

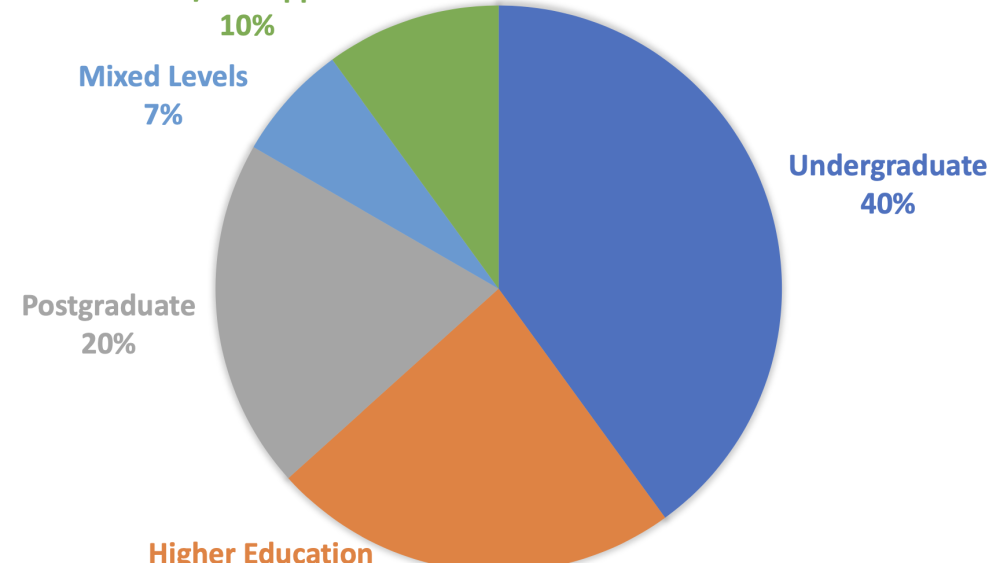

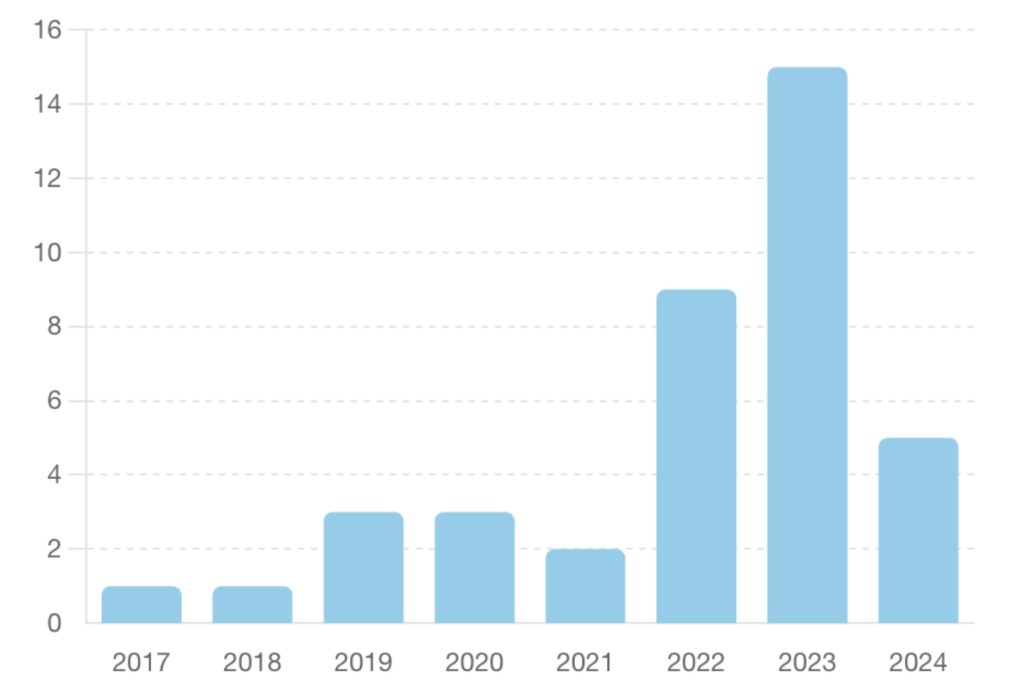

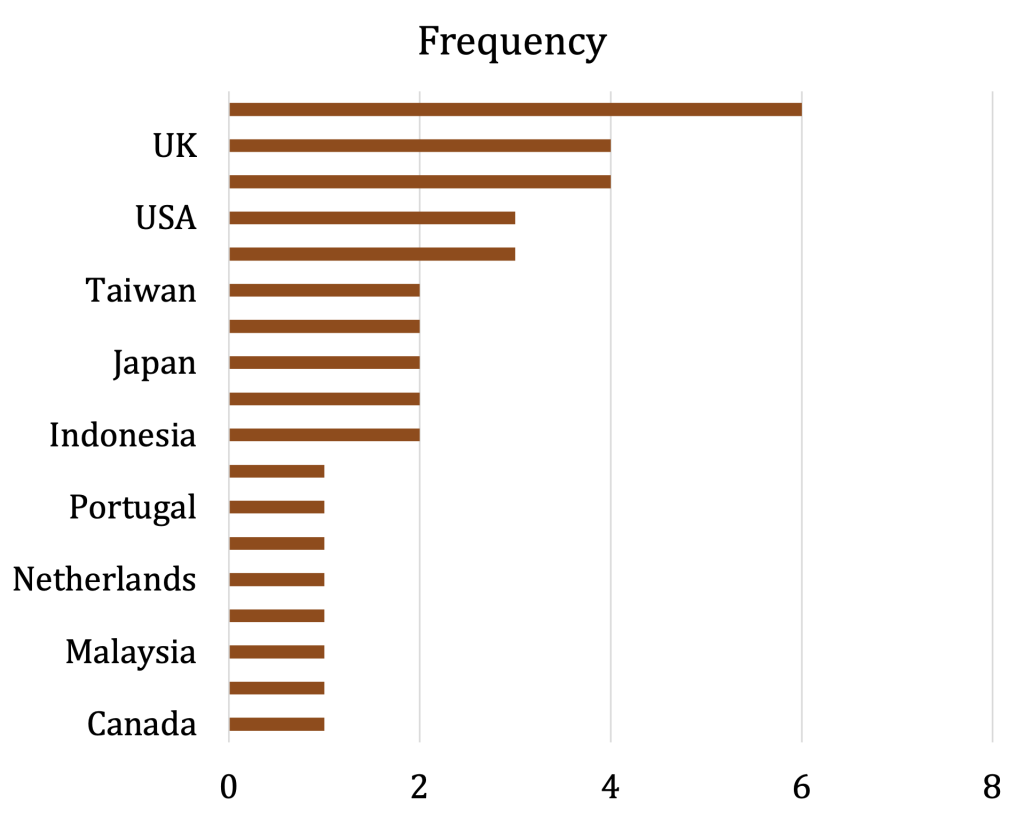

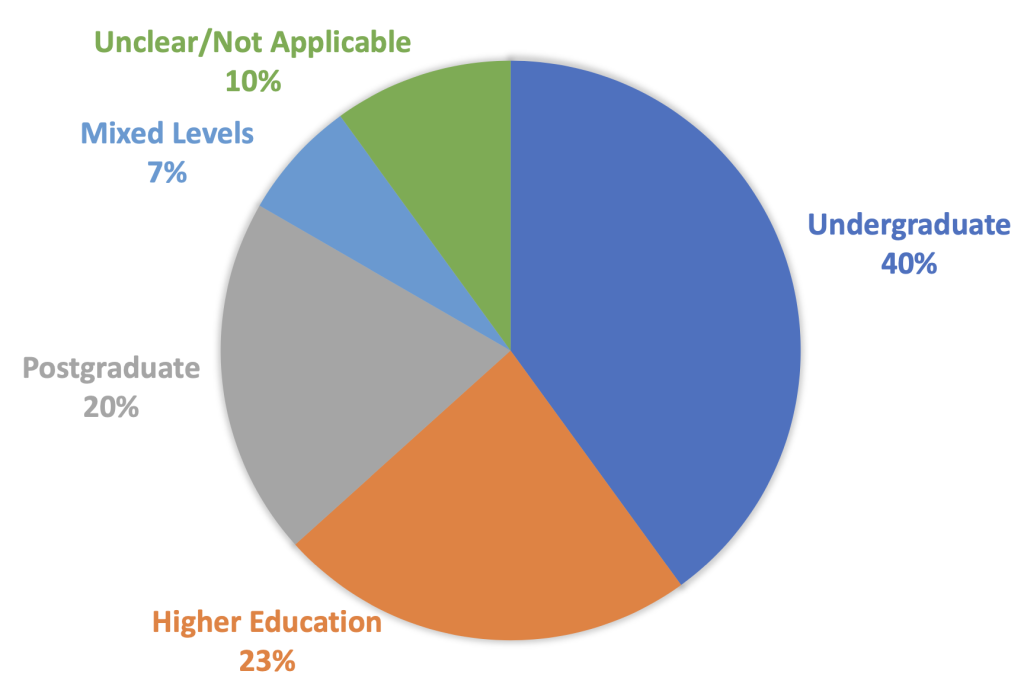

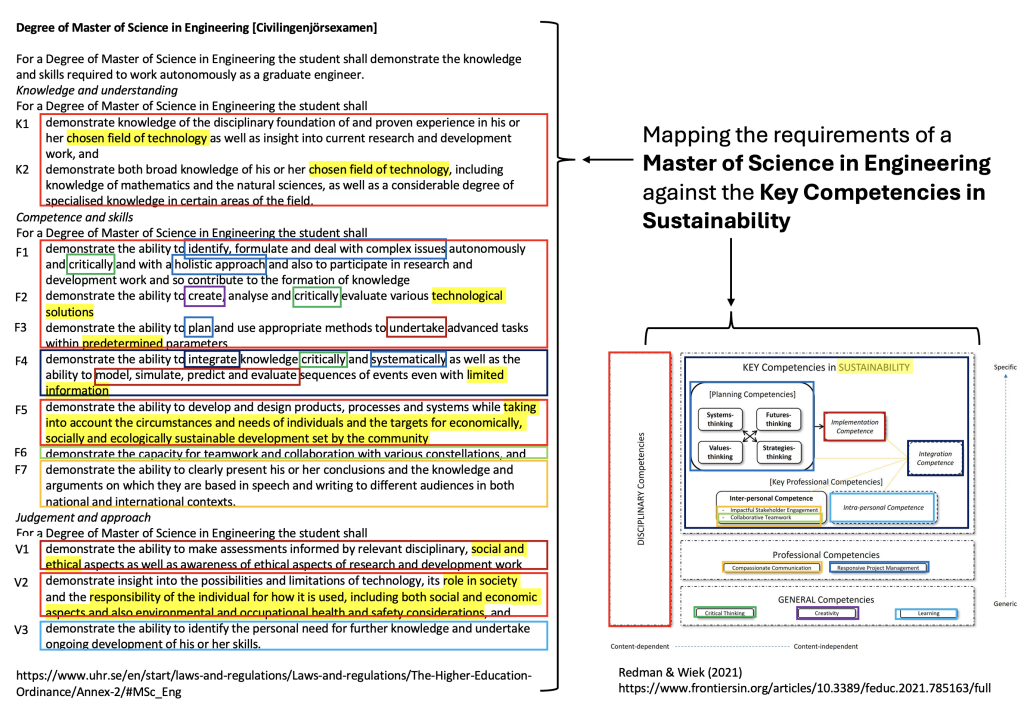

To start, we scoped the literature and read a few review articles on the topic of sustainability. To reduce the number of results, the scoping study revolved around the keywords sustainability, education, and engineering. The search was also limited to journal articles which were in English. The second screening was then based on our own subjective screening of article titles and abstracts – this left us with nine articles we thought would be the most relevant for us; see Table 1. The articles gave us a basis for research on the topic of sustainability education (as well as its other variations education for sustainability and education for sustainable development). Included in this research were some key learning outcomes and educational approaches which supported teaching for sustainability. However, the articles usually stopped short of providing concrete support of precisely how we could implement our seminar. This is where the latter two methods compensated.

We were not able to perform an exhaustive systematic review of each of the nine articles. However, based on our preliminary and unstructured review, we have identified the following key insights:

- Education for sustainability is essentially good teaching, i.e., not something ad-hoc or external to our courses. This makes it quite relevant for all our courses.

- Some general frameworks or guidelines for implementation seem to exist, which can highlight some useful practices, teaching approaches and learning outcomes. However, it is not always clear for us (the teaching laymen) what this means specifically for our courses.

- There are many people out there doing this kind of teaching with some good results. However, it is often difficult to grasp the specifics as the articles may be on a higher level and when cases are presented, we may not easily see how our specific courses could benefit from what was described.

- When concrete cases are provided, these can be very revealing (peeling away the abstract to reveal something tangible and concrete). It can provide inspiration for what to do with some added confidence that comes with seeing the results it provided. Now, we should be careful to generalize, but our own experience is that we as teachers need to braver in applying new things in our courses.

- As teachers our focus is often on our own courses, but the issue also needs to be addressed at higher levels (e.g., integration into program curricula). Perhaps this is a calling for us to try and influence the administration in these questions. In any case, we think a bottom-up and top-down approach should occur simultaneously (and ideally somewhere in there are the wishes of the students).

- At the face of it, sustainability as a concept appears complex with multiple components (pillars, etc). On the other hand, it is perhaps not necessary to try and incorporate all of these into all our courses. Choose those aspects which you find most relevant or exciting.

We also sought inspiration from colleagues who had more experience with sustainability in their courses. In total, we discussed and took notes with three other teachers, for about an hour each. We both took notes during the sessions and cross checked afterwards to summarize whether we came to the same conclusions. The discussions provided us with some inspiration as to how teaching for sustainability could be achieved and helped shape our perspectives towards the task at hand. We also came up with some concrete examples, or case studies, that could be included in our seminar. Now that we had a firmer basis for proceeding, we started to focus more specifically on how we should plan our own seminar.

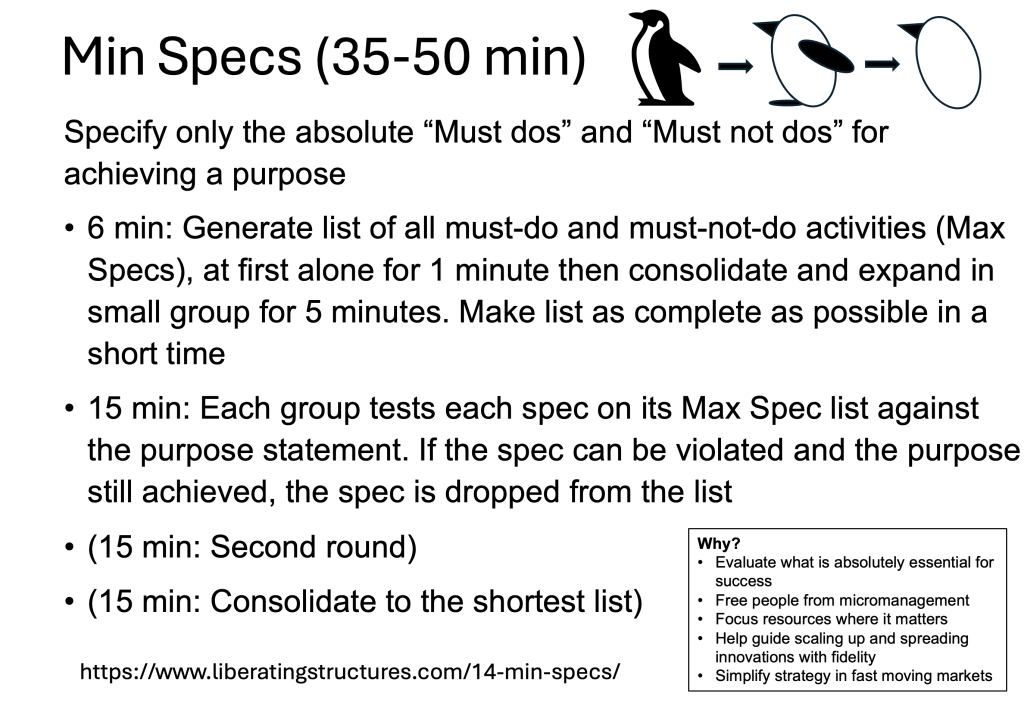

As a third method we utilized internal brainstorming sessions to come up with a concrete plan for how the seminar could be implemented. These sessions took place at the end as we then had a better understanding of the concept of teaching for sustainability as well as to identify possible case studies. Thus, we started by asking ourselves what it is we want our students to experience and learn during the seminar. As this was to the steppingstone for future developments, and as we wanted to facilitate a shared learning experience (teachers & students), we also concluded that it would be important to document how the seminar went and to disseminate lessons for the next course iteration. This final aspect is critical as we have the possibility to adjust more in the course than simply one seminar the following year. The outcome was a concrete plan for the seminar which would include two external observers helping us with post-seminar reflections. The students would also be required to provide reflections – which is another promising source of further development.

Seminar plan

Our objective is to design and implement a 2-hour active learning seminar integrating sustainability as a key complementary aspect to consider in the design of structures, specifically structural engineering design. We want to provide the students with some basic building blocks to enable them to reflect about how their design choices affect sustainability, and how structural safety can be achieved without excess material use. In this way we hope to also help normalize the discussion about sustainability and hopefully also provide some inspiration for doing the same in other courses. As we intend to implement this in an ongoing course (this semester) we also hope to learn some valuable lessons along the way. The seminar is intended to support the following learning outcomes:

- The students shall have a broad understanding for sustainability as a concept.

- The students shall be able to identify how structural engineering design and verification decisions in terms of their sustainability impacts.

- The students should be able to discuss these issues with their peers, in groups, and with the teachers in the course.

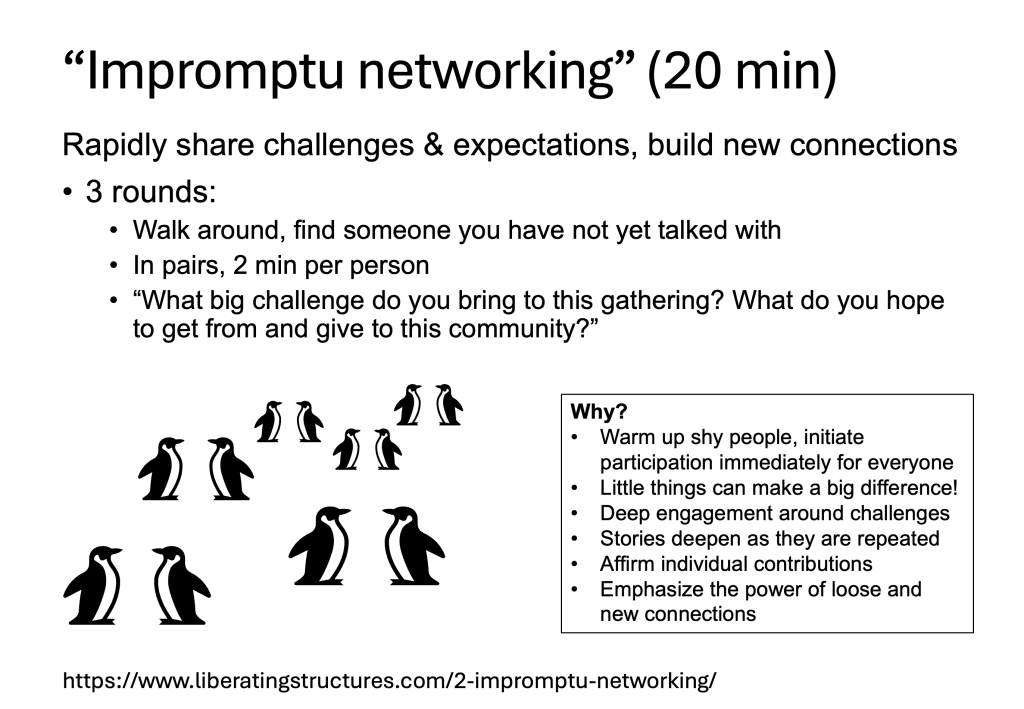

In planning the seminar, we have relied on previous experiences with (1) active learning methods, and (2) the use of the case method in teaching. The former is rooted in the concept of experiential learning (originally formulated by Kolb), is well-known for improving engagement, and can improve student learning2 [11]. Active learning can be briefly defined as instructional activities involving students in doing things and thinking about what they are doing [12]. The latter is, as the name suggests, about a ‘case’. Cases help facilitate learning problem-solving; the characteristics of the cases used are thus inherently connected with the types of problems to be solved and ultimately the intended learning objectives [13]. The case method is usually conducted in seminars and the teachers’ active participation is central to guide the students and to support learning [14].

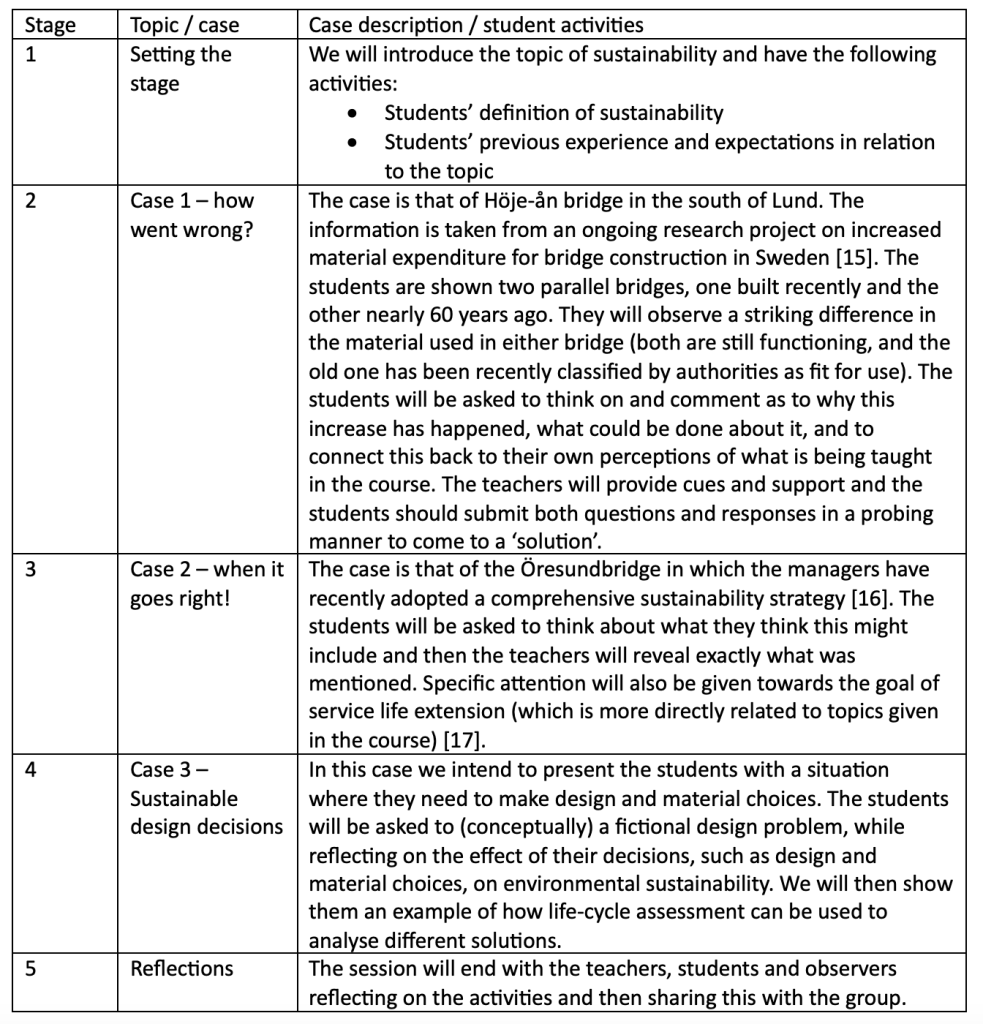

An overview of the seminar is provided in Table 2. Three cases were included, chosen to support the learning outcomes. The student activities included think-pair-share in groups of two to three, followed by larger group discussions at each table. We, the teachers, then positioned ourselves in a larger discussion based on input from some of the groups. To facilitate participation, we sometimes collected responses using the interactive presentation tool Mentimeter (mentimeter.com). During the seminar, we also allow students to ask questions through the Q&A function to ensure any unanswered queries are communicated and addressed. As teachers we adopted the attitude of co-learners with the students and try to communicate this early on and throughout. Although we still need to moderate the class, we highlight for the students that their answers may be just as relevant and perhaps even more so than our own – we are in it together, navigating a wicked problem that has no single right answer. The cases are also chosen to provide some personal connection to the teachers – who are either directly involved in the research or got the information from very close colleagues

After the seminar, the teachers and observers have a quick discussion to summarize their findings and identify important lessons for improving the concept and for making broader changes to the course (and perhaps even other courses).

Results & lessons

This section summarizes our own reflections from the seminar as well as input from the observers.

There was a low number of participants in the seminar in relation to the total number of students in the course. We were able to put together three groups of students, each having about four students. The low number of participants was not surprising as the seminar was voluntary, was placed at the end of the course near the exam and the topic was not included in the course syllabus (kursplan). This can be improved for next years by including the topic in the course syllabus.

The student engagement for the topic was positive and the observers commented that the teachers were approachable. It was also mentioned that having two teachers was good as it demonstrated for the students that it was acceptable to participate and even disrupt if they had something they wanted to say (as this was the dynamic we had with each other as teachers). As a result, we did not observe much of an issue in discussing this challenging topic and in that way thought it helped normalize the discussion. It should be noted that the low number of participants may have had a positive impact on this aspect, as it may be easier for students to voice their ideas in a smaller group.

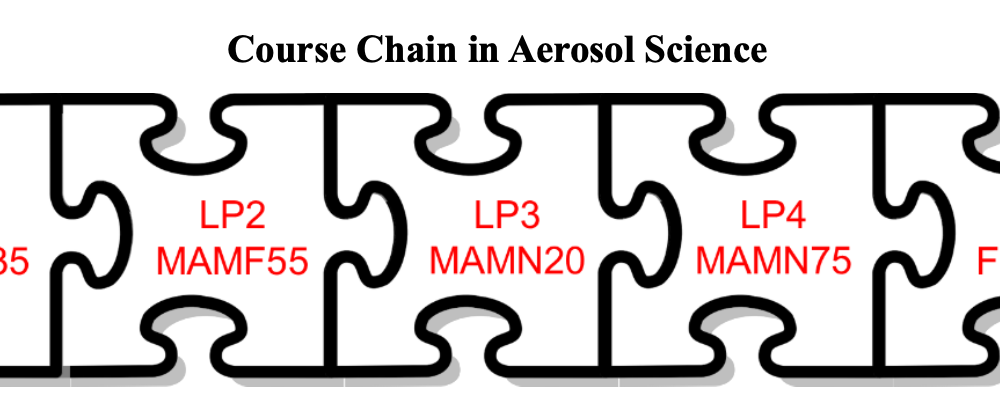

The seminar revealed for the teachers that the students had some prior knowledge on the topic, and this was a way to reinforce the importance of this topic in later courses in the program. This made us realize that we need to learn more about the exact background they have in the subject based on the previous course they took. For future development, we see potential in making more explicit connections between our examples and knowledge from previous courses, thus reinforcing the idea of course alignment.

The primary focus was on environmental or ecological sustainability while the other pillars were less prominent. This is most likely as our examples were quite focused on this – we could do better in the future. In the discussion with the observers, it was also highlighted that it would be better to talk about the subject in more specific terms rather than the overall subject of sustainability. For example, we can say ecological sustainability directly, and then possibly include discussion topics connected to the other pillars of sustainability (social and economic).

Some specific ideas for how we could improve this next year:

- Change the course plan for the course to include sustainability in some way (most likely the focus will be on environmental sustainability as this is very relevant for the topic of study)

- Make smaller changes to the lecture material to have some connections to sustainability throughout (e.g., by referring to SDGs)

- Include sustainability considerations and incorporate relevant tasks in the project work (while trying not to have it as something ad-hoc or supplementary).

- Further develop the seminar concept and include other pillars of sustainability (e.g., indoor climate issues can lead to health issues for users)

As a final note, it should be emphasized that these reflections focus primarily on a particular seminar format, and how this can be improved for next years. In parallel, we have discussed other ways to integrate sustainability in the course. For example, it may be favorable to integrate sustainability aspects in other lectures and seminars instead of having a dedicated session. After all, sustainability is a multifaceted concept that intersects with most topics in structural engineering

References

[1] United Nations Environment Programme (2024). Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction: Beyond foundations: Mainstreaming sustainable solutions to cut emissions from the buildings sector. Nairobi. https://doi.org/10.59117/20.500.11822/45095.

[2] Holdsworth & Sandri (2021). Investigating undergraduate student learning experiences using the good practice learning and teaching for sustainability education (GPLTSE) framework. Journal of Cleaner Production, 311, 127532.

[3] Gutierrez-Bucheli, Kidman & Reid (2022). Sustainability in Engineering Education: A Review of Learning Outcomes. Journal of Cleaner Production, 330, 129734.

[4] Oswald Beiler MR & Evans JC (2015). Teaching sustainability topics to attract and inspire the next generation of civil engineers. Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice, 141(2), C5014001.

[5] Tejedor G et al (2019). Didactic strategies to promote competencies in sustainability. Sustainability, 11(7), 2086.

[6] Hensley N (2020). Educating for sustainable development: Cultivating creativity through mindfulness. Journal of Cleaner Production, 243, 118542.

[7] Kevern JT (2011). Green building and sustainable infrastructure: Sustainability education for civil engineers. Journal of Professional issues in engineering education and practice, 137(2), 107-112.

[8] Riley DR, Grommes AV & Thatcher CE (2007). Teaching sustainability in building design and engineering. Journal of Green Building, 2(1), 175-195.

[9] Viegas CV et al. (2016). Critical attributes of Sustainability in Higher Education: A categorisation from literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 126, 260-276.

[10] Barth M & Rieckmann M (2012). Academic staff development as a catalyst for curriculum change towards education for sustainable development: an output perspective. Journal of Cleaner production, 26, 28-36.

[11] Freeman S et al. (2013) Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. PNAS, 111(23), 8410-8415

[12] Bonwell CC & Eison JA (1991). Active learning: creating excitement in the classroom. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Reports.

[13] Jonassen DH (2011) Learning to Solve Problems – A Handbook for Designing Problem-Solving Learning Environments. Routledge: Taylor & Francis Group, New York.

[14] Maufette-Leenders LM, Erskine JA & Leenders MR (1997) Learning with Cases, 2 ed. Ivey Publishing, London, Ontario.

[15] Björnsson I et al. (2024 – submitted) Resource expenditure for bridges in Sweden – do we build greener bridge now compared to 50 years ago? IABSE Congress San Jose 2024 – Beyond Structural Engineering in a Changing World.

[16] Boykova E (2023). Forward charge. Bridge Design & Engineering, 111, 72-73.

[17] Björnsson I, Thöns S, Celati S & Hergart B (2024). Towards a service life extension of the Øresund Fixed Link. IABMAS 2024, 24-28 June, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Comments